Undocumented renters caught between fire and ICE in LA burn zone

A construction crew, comprised of Hispanic men, starts work rebuilding a home in West Altadena, an ethnically mixed neighborhood where emergency evacuation warnings failed during the January Eaton Fire. August 12, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons

What’s the context?

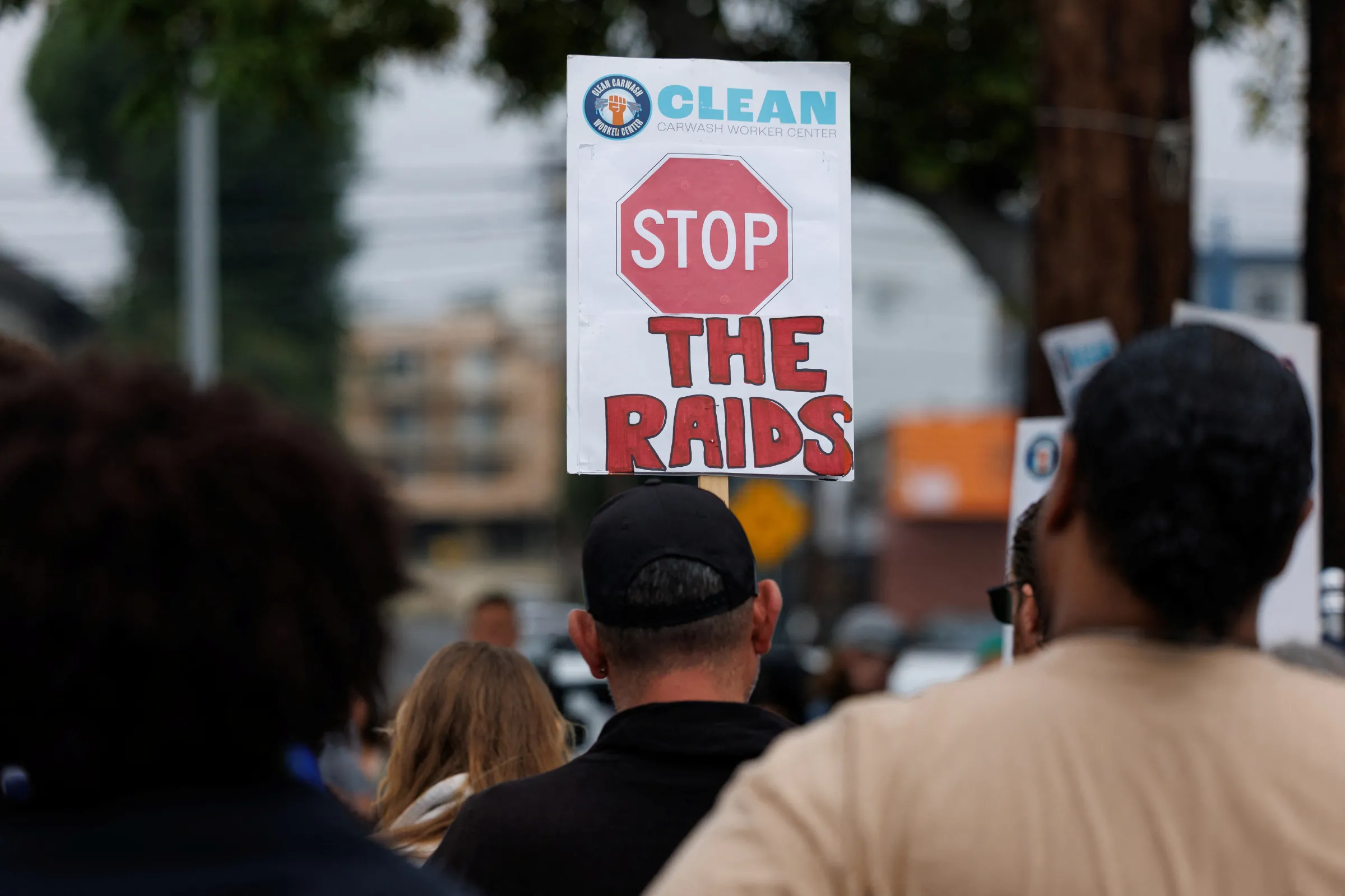

Undocumented renters still recovering from Los Angeles wildfires have become targets for ICE raids.

- Fire victims facing increased exposure to ICE raids

- County to launch cash assistance fund for immigrants affected by raids

- Immigrant labor essential to rebuilding after fires

LOS ANGELES - Blanca and her family fled a deadly wildfire in January that devastated her Los Angeles area neighborhood and burned the clothing alterations business she owned for six years to the ground.

Her rented apartment in Altadena was spared but uninhabitable, with no gas, electricity or hot water, and contaminated with toxic ash and soot.

But she was ineligible for federal assistance for her business or her home because she is undocumented.

Now 48, she came from Mexico more than 20 years ago with one child.

After the fire, she and her family lived in temporary housing while she and her neighbors battled with the apartment building manager to clean and repair their ruined homes.

President Donald Trump ordered a crackdown on undocumented immigrants in late January when he took office.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents descended on Los Angeles, making thousands of arrests in the following months.

While ICE initially was not rounding up residents in burn zones, that has changed.

![‘ICE out of …’ campaigns have sprung up throughout Los Angeles County since federal immigration raids have ramped up over the summer. An ICE Out of [Alta]Dena sign is posted in a bilingual Spanish and English business that survived the Eaton Fire, August 12, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons](https://ddc514qh7t05d.cloudfront.net/dA/628a21d56a883e7abf24f2f00af22f99/2400w/80q)

‘ICE out of …’ campaigns have sprung up throughout Los Angeles County since federal immigration raids have ramped up over the summer. An ICE Out of [Alta]Dena sign is posted in a bilingual Spanish and English business that survived the Eaton Fire, August 12, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons

‘ICE out of …’ campaigns have sprung up throughout Los Angeles County since federal immigration raids have ramped up over the summer. An ICE Out of [Alta]Dena sign is posted in a bilingual Spanish and English business that survived the Eaton Fire, August 12, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons

In June, ICE agents raided a burned property in Altadena, targeting the construction crew, and they have conducted random traffic stops and used racial profiling to apprehend people throughout the county.

For residents without legal status, the one-two punch of a devastating fire and the threat of deportation has become unbearable.

"It's too much stress, too many emotions to work through," said Blanca, who did not want her surname used, wiping away tears.

"There wasn't time to recover from the fire," she said.

More than 900,000 undocumented residents live in Los Angeles County, according to data from the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute.

The January conflagrations in Altadena and the Pacific Palisades areas destroyed more than 16,000 structures and killed at least 30 people.

Undocumented renters are already at higher risk of eviction and abuse by unethical landlords, and many who lost their homes in the fire now live in neighborhoods where ICE raids are more frequent, according to county officials.

Displaced tenants are forced to live “in neighboring communities where aggressive immigration sweeps … have intensified anxiety and instability for these vulnerable residents," said Hilda Solis, a member of the county Board of Supervisors.

"As the only Latina on the Board of Supervisors and the daughter of immigrants, these raids strike a deeply personal chord," she added.

When Blanca returned to her apartment in May it had been stripped of even its appliances and furniture. The building's gates have not been repaired, leaving the property unprotected.

She carries bear spray when she travels to her temporary job as a caregiver because ICE agents on the street wear masks and present no identification.

"We’re not sure it's ICE and not a bounty hunter," she said. "We can't even go to work comfortably."

Federal ICE agents arrested more than 2,200 people in the Los Angeles area in June alone when raids ramped up and the Trump administration ordered military units brought in to assist agents and put down protests.

Neglected renters

Katie Clark, co-founder of the Altadena Tenants Union, said regardless of legal status, renters in the fire zones have been neglected by local and federal governments compared with the support going to homeowners.

Even before the Eaton fire burned through Altadena, killing 19 people and destroying some 9,600 buildings, renters lacking legal status or in mixed-status households were at risk of exploitation.

Undocumented renters tell of landlords and building workers threatening to report them to ICE if they complained about repairs or maintenance.

"For all of our undocumented neighbors, we see them as even more vulnerable than they were before the fires," Clark said.

"Certainly these overlapping crises have only intensified their situations."

The tenants union has sued Los Angeles County to force the public health department to inspect rental properties and compel landlords to conduct fire remediation and meet financial obligations.

In the fires' aftermath, the county launched a six-month moratorium on evictions and a $32.2 million financial relief fund for renters and homeowners, according to a spokesperson for County Supervisor Kathryn Barger.

Legal status was not part of the eligibility criteria, she said.

The application window was open for two weeks in late February.

"Renters who lost their housing or income in this disaster deserve access to every available resource, from financial relief to legal protections. My commitment is to keep fighting for the support they need to rebuild their lives,” Barger said.

No place else to go

Some of Blanca's neighbors returned to their apartments in February before they were cleaned because they had no place else to go, living without heat or even windows.

They were exposed to dangerous levels of lead and other carcinogens from ash for months, according to data from the county public health department.

The lot where Blanca’s business was stands empty, waiting for reconstruction by a dwindling labor force that is targeted by daily immigrations sweeps throughout L.A. August 12, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons

The lot where Blanca’s business was stands empty, waiting for reconstruction by a dwindling labor force that is targeted by daily immigrations sweeps throughout L.A. August 12, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons

Officials have encouraged anyone living in or near the burn scar to have their blood tested for lead poisoning.

But many people, including Blanca, have foregone medical appointments and other day-to-day activities to limit their risk of getting caught by ICE.

Owning a business and paying taxes, Blanca said she felt secure but not anymore.

"If there's one thing I valued or respected in this country, it was how safe I felt," Blanca said.

Immigrant labour

Most burned lots have been cleared and sit ready for new homes and businesses.

Rebuilding is slow, however, because the construction industry relies on skilled migrant workers, the very people being targeted by ICE.

"There's no way that you can rebuild Altadena without migrant labor, without the undocumented immigrants," said Pablo Alvarado, co-executive director of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network which supports workers rights.

The Board of Supervisors in July approved a motion, authored by Solis, to create a cash assistance fund for residents affected by immigration raids and expand an existing assistance program for small businesses, but details are scant and it is unclear when the programs will start.

No state assistance has been earmarked for those targeted by the raids.

(Reporting by Rachel Parsons. Editing by Anastasia Moloney and Ellen Wulfhorst.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Government aid

- Housing

- Climate inequality

- Migration

- Loss and damage