Afghan women judges urge world to help after Taliban death threats

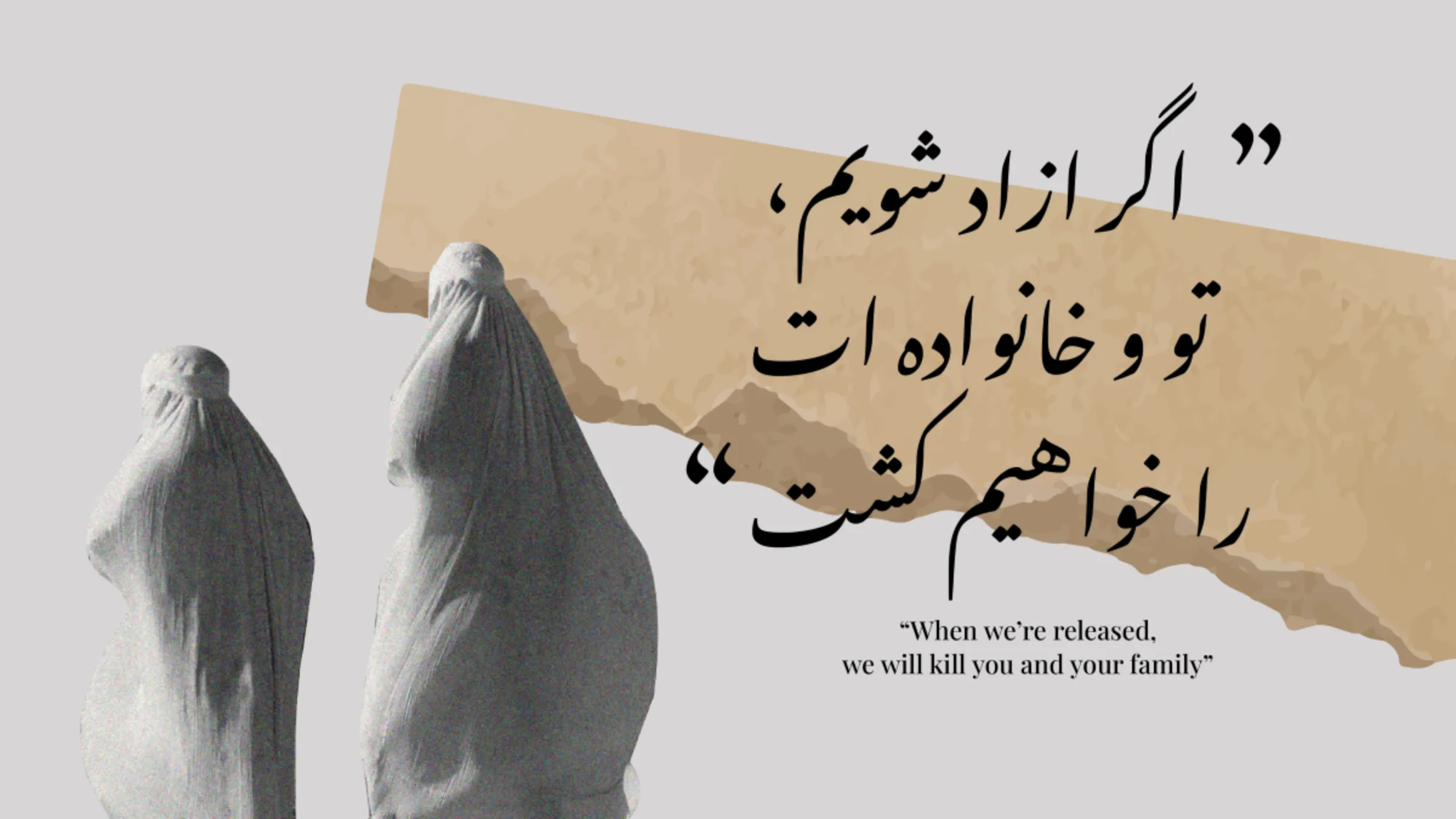

Two Afghan women walk next to the words "When we're released, we will kill you and your family" in this illustration picture. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Nura Ali

What’s the context?

Women judges living in fear of militant reprisals in Afghanistan plead for help to escape country

- Female judges living in hiding since 2021

- Afghan judges say world has forgotten them

- UK lawmakers call for emergency visas

LONDON - In her long career as an Afghan judge, Sara helped lock up scores of Taliban militants for deadly attacks, ranging from bomb blasts to assassinations - now freed from jail, they have vowed to hunt her down.

"When the Taliban seized power, they opened the prison gates. I've lived every day since then in panic and fear," Sara told Context from a secret location where she lives with her children and husband.

Sara is among dozens of women judges in hiding since the hardline Islamist group seized control of Afghanistan on Aug. 15, 2021.

They have received countless death threats in phone calls and WhatsApp messages, and said their old homes had been repeatedly raided by Taliban members.

"During my career, prisoners warned me, 'When we're released, we will kill you and your family'. Even now just talking about this, I'm shaking with fear," said Sara who, like other judges in hiding, used a pseudonym for security reasons.

When the Taliban took over Afghanistan there were about 270 women judges. At high risk of reprisals, most escaped in the chaotic aftermath of the takeover - some in a rescue mission part-funded by Harry Potter author and philanthropist J.K. Rowling.

Many are rebuilding their lives in new countries including Canada, Germany, the United States, Britain and Australia.

But Marzia Babakarkhail, an Afghan former judge now living in Britain, said about 50 remained trapped in Afghanistan while nearly 20 were stranded in neighbouring Pakistan where they live in terror of being deported and handed over to the Taliban.

"It's only a matter of time before one of these judges gets killed," said Babakarkhail, as she appealed to Western governments to help get the women to safety.

Babakarkhail, who moved to Britain in 2008 following two assassination attempts by militants, said the women felt betrayed by the international community after risking their lives to fight for justice.

"I'm completely incensed at the way they have been abandoned," she said. "I'm urging every country to resettle them, but they're all closing their eyes to this."

British petition

This week, British lawmakers will present a petition to the UK parliament demanding the government help evacuate and resettle the judges by providing emergency visas.

Lawmaker Joanna Cherry will also meet Prime Minister Rishi Sunak on Wednesday to ask him to "bang heads together" to help get the judges out.

"Britain has a moral obligation to these women," she said.

"We went into Afghanistan, we tried to set up a Western style rule-of-law democracy, we encouraged women to become prosecutors and judges, and when we pulled out we left them high and dry."

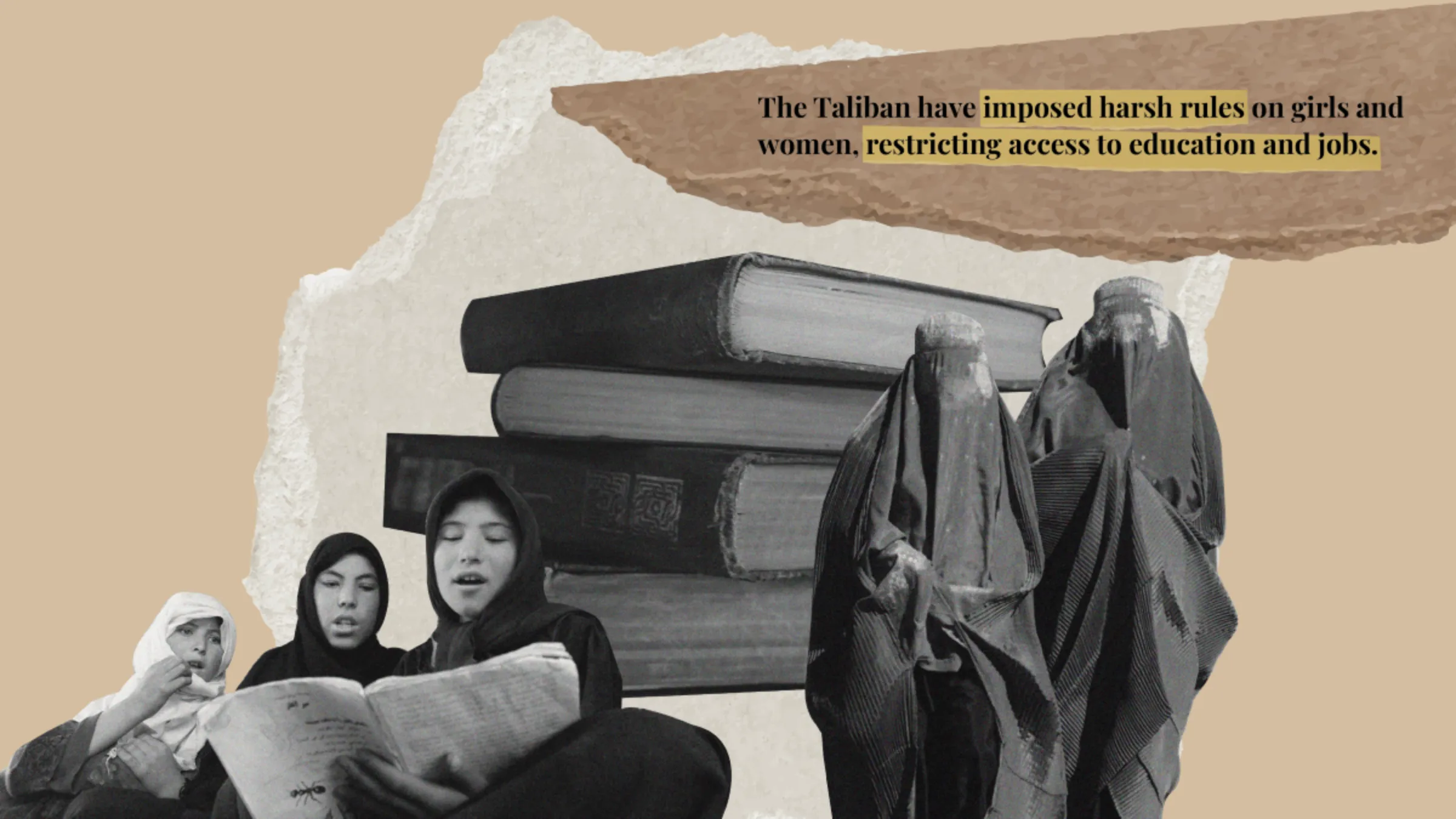

A group of Afghan schoolgirls read as women walk by in this illustration picture. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Nura Ali

A group of Afghan schoolgirls read as women walk by in this illustration picture. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Nura Ali

The judges are not only at risk from released criminals including drug traffickers and murderers, but also because of their trailblazing role in defending women's rights.

Many worked in family courts helping women seeking divorces from abusive husbands, and in specialised courts set up across the country to tackle pervasive violence against women.

The courts are defunct under the Taliban, who have reversed 20 years of Western-backed efforts to boost women's rights in the deeply patriarchal country.

They have barred girls from high schools, banned women from most jobs and imposed draconian restrictions on their daily lives.

Taliban officials did not respond to requests for comment.

Database fears

Once proud breadwinners for their families, the judges are now living in poverty. Some face increasing violence from family members who accuse the judges of putting their own lives at risk.

Chronic stress and depression have left some suicidal, and several have tried to set themselves on fire or take overdoses, Sara said.

Her family spent months on the move and are now cooped up in a shabby, cramped property where the curtains are kept shut.

"I've had to sell everything just to survive, even my wedding ring," said Sara.

She has also pulled her children out of school for security reasons.

"They're always at home like prisoners," she said. "It hurts a lot to see them like this, but I can't do anything about it."

Sadaf, a judge from outside Kabul, said the Taliban had access to a database containing the judges' phone numbers, addresses, photos and information about their families.

She has received many death threats from Taliban members she convicted in domestic violence cases.

Before the takeover, Sadaf was optimistic about her country's future and hoped to run for parliament.

"The situation is becoming more critical by the day. House searches continue, the killing of former government employees continues," she said.

"There are so few female judges in Afghanistan that everyone knows us. Anyone could hand us over."

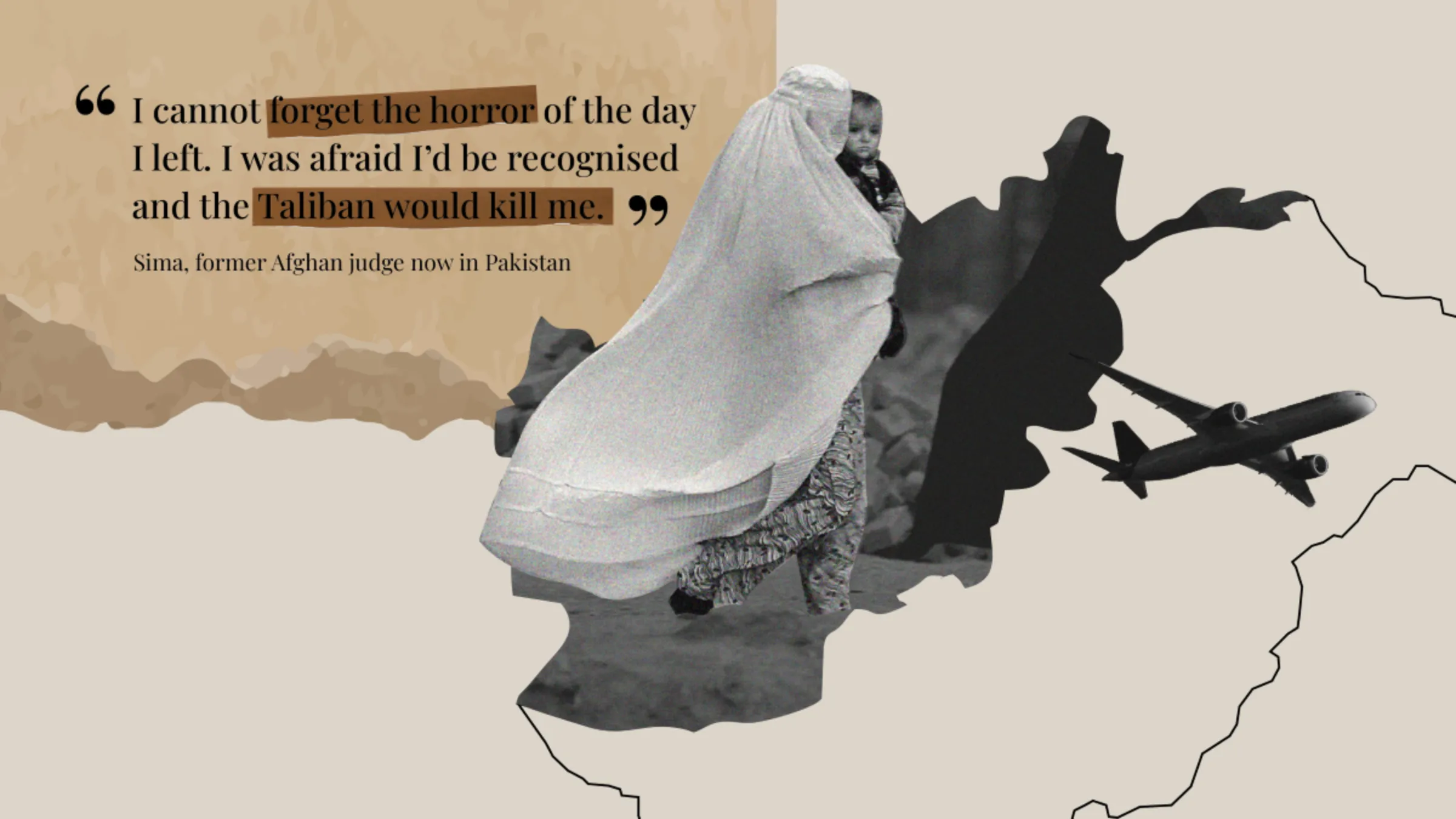

An Afghan woman carries a baby in this illustration picture. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Nura Ali

An Afghan woman carries a baby in this illustration picture. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Nura Ali

Some of the judges have fled to neighbouring Pakistan, hoping to get help to move to other countries. However, Pakistan has not agreed to recognise newly arriving Afghans as refugees, leaving them vulnerable to deportation.

Sima, a judge from Kabul, entered Pakistan last year via the Torkham border crossing, but her visa has expired. She said the only way to get a new visa was to exit Pakistan and re-enter.

"All the judges in Pakistan have overstayed," she said. "But we can't go to Torkham because if the Taliban recognise us, they'll kill us."

Afghan refugees in Pakistan frequently complain of police harassment and demands for bribes.

Police chiefs say officers have been ordered not to hassle Afghans, but Sima said her husband had been detained twice even when their visas were valid. Now they have expired, the family are even more fearful.

The U.N. refugee agency (UNHCR) said it was continuing discussions with Pakistan on measures to protect vulnerable Afghans, but there was no progress.

'Empty promises'

The International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ), which helped organise the 2021 evacuations of many of the judges, said it was still trying to find solutions for those who remained.

IAWJ president Susan Glazebrook said the judges faced a Catch-22 situation as they could not have visa applications processed until they left Afghanistan, but crossing to neighbouring countries could leave them more vulnerable.

"It's becoming more and more difficult, but we won't give up," she said.

Legal experts said the best bet for judges in Afghanistan might be a new scheme launched by Germany last October to take in thousands of people at high risk who are still in the country.

However, they said the programme was cumbersome and Germany had recently frozen its admission procedures for Afghans due to security concerns.

Like many other judges in Pakistan, Sima is hoping to join a U.S. resettlement programme, but there is a massive backlog of applications. Matters are complicated by the fact there is no U.S. processing centre in Pakistan.

"We've had nothing but empty promises from everyone," she said.

This story was updated on Wednesday May 3, 2023 at 11:10 GMT to reflect the changed date of when a petition will be presented to lawmakers in paragraph 12.

(Reporting by Emma Batha and Orooj Hakimi; Editing by Jon Hemming.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Gender equity

- Government aid

- War and conflict