Climate-hit South Asian countries need a health system overhaul

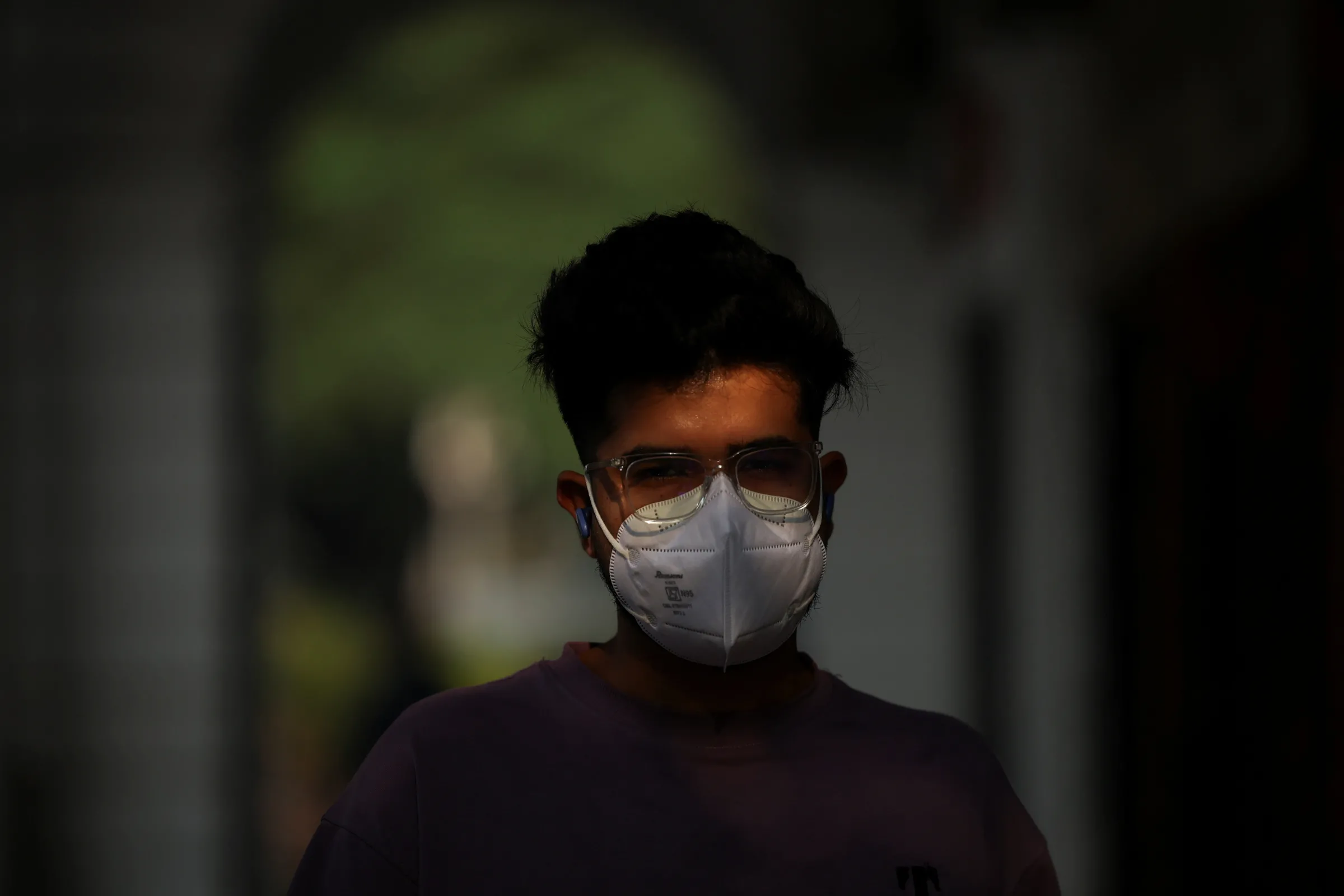

A man runs in front of India Gate on a smoggy morning in New Delhi, India October 31, 2025. REUTERS/Adnan Abidi

People in the Global South are disproportionately affected by fossil fuel pollution. Climate finance needs to help them adapt to the challenges.

Harjeet Singh is an activist advocating for climate and social justice globally, and the Founding Director of the Satat Sampada Climate Foundation.

The climate crisis is wreaking havoc and taking an increasingly devastating toll on people’s health across the planet, while the world is falling short of cutting its greenhouse gas emissions, thanks to escalating investment in fossil fuels.

A recent ActionAid study shows that fossil fuels and industrial agriculture are receiving subsidies worth $677 billion in the Global South, leaving a disproportionate and multidimensional adverse impact on people in climate-vulnerable regions like densely populated South Asia.

About 1.6 billion people live near places where fossil fuel burning emits heavy amounts of PM2.5 and other toxins.

The threat posed by fossil fuel pollution is not evenly distributed; rather, people in the Global South are the most exposed to its impact. Among pollution-related deaths, 92% occur in the lower and lower-middle-income countries. Large South Asian cities like Delhi, Dhaka, or Lahore rank among the most polluted cities. The growing air pollution in these cities is directly linked to more burning of fossil fuels.

Beyond direct pollution-related harms, coal, oil, and gas account for 75% of the global greenhouse gas emissions and are thus the biggest contributors to the global climate crisis. The world now sees more frequent and intense disasters that damage critical infrastructure and disrupt health services. In the coastal and inland areas of India and Bangladesh, floods spread communicable diseases like cholera, while growing salinity contributes to increased cases of hypertension as well as pre-eclampsia for pregnant women.

Millions of people lack safeguards from the two-fold harm caused by fossil fuels - pollution and climate-induced disasters, as low-income countries spend just about 2% of their GDP on the health sector and thus are not ready to tackle the health impacts of fossil fuels.

For Bangladesh, it is 2.39% while India is slightly better with 3.39%. The health infrastructure and services are under-resourced to meet the needs of people on the climate frontline, while the same fragile system gets ravaged by climate-induced disasters, creating a double jeopardy.

More planning, more resources needed for health system adaptation

Countries and cities need to strengthen their under-resourced and dilapidated health infrastructure anyway, and now with the climate emergency, we need to put in more funding.

Health considerations should be woven into the national development and climate plans, ensuring seamless coordination across ministries and departments at the national and local level: harnessing the synergies among disaster management, climate action, health care, and infrastructure building.

Developing countries are still only building the basic health infrastructure, and they can grab the opportunity of making it resilient right from the beginning. National and local governments need to build climate models reflecting climate risks into their planning process, forecasting what a 1.6 degree warmer climate could mean for their infrastructure. The infrastructure should integrate adaptive capacity, ready to provide services amid the worst-case scenarios.

The costs of climate-related health care are growing, and will reach $9-$15 trillion by 2050. With an annual adaptation finance gap of $187-359 billion, developing countries cannot solely rely on global funds like the Green Climate Fund and Adaptation Fund, but need to make the best use of their own limited resources.

Public finance has to be mobilised for funding critical health system adaptation, because the private sector’s role in building community capacity for adaptation has been limited, and privatization often hampers the provision of critical health services at the community level. Most of the onus of primary health care should be placed on the government, as health care is a fundamental right.

Linking the local and the regional

With a more locally led approach, health care should be decentralised, making primary health care much more accessible to the people living on the frontline. As exemplified by Nepal’s local adaptation plan of action (LAPA), local administrations across South Asia should create and implement their own adaptation action plans in line with vulnerability and risk assessments. Adequate resources should be delegated to communities and hospitals to tackle the known risks.

Community awareness needs to be built about the health risks and how these are linked to the burning of fossil fuels and climate change. It is a two-way street. Local communities are best able to identify what kind of risks and hazards they face during disasters, and the government should design the adaptation response in line with that knowledge. A large body of local health workers has to be trained to ensure last-mile connectivity, while the health care system should also address inequality and inequity built into social categories like caste, gender, and age.

South Asia is expected to face about a quarter of the deaths due to climate impact while losing 1.2 to 2.8 percent of its regional GDP due to economic loss and damage. It is time for climate-vulnerable South Asian countries to step up their work on the growing health challenges coming from climate-induced disasters and pollution. They need to work closely with each other across boundaries - from ensuring cross-border early warning systems to having a broader regional approach to disease outbreaks.

Richer countries with historic legacies of greenhouse gas emissions must step up and take urgent actions to tackle the growing health care challenges during the COP30 and beyond. These include providing more climate finance for adaptation in Global South countries, with comprehensive programme-level support to make their health systems more resilient.

Adequate finance should be delivered transparently on time, allowing easy access. A fair sharing of the health care costs could go a long way towards ensuring a just adaptation to climate impacts.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5