Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Eleni Myrivili, global chief heat officer for UNEP, is pictured on Filopappou Hill in Athens, Greece, in 2023. Irene Vourloumi/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Ahead of COP30 climate summit, U.N. chief heat officer Eleni Myrivili urges radical rethink on how we design our cities.

LONDON - From Athens to Delhi, soaring global temperatures are turning cities into infernos with deadly heatwaves putting lives and livelihoods at risk.

Cities can be 5-10 degrees Celsius hotter than surrounding areas due to the urban heat island effect.

By 2050, more than 1.6 billion people living in some 1,000 cities could face intense heatwaves, climate experts say.

To help cities adapt, a major drive called Beat the Heat will be launched at the United Nations COP30 climate summit in Brazil on Nov 11, bringing together governments, city mayors, urban planners, big tech and other key partners.

The U.N.'s chief heat officer, Eleni Myrivili, spoke to Context about how we can cool our cities.

The summer has radically changed this decade. We're now getting at least one long, intense heatwave every year, with days often above 40 degrees.

Above 35 degrees, it's very hard to function, work, move around or even sleep because the city doesn't cool down at night.

It can be deadly. In Athens, 20% of our population are over 60. A lot of people die during extremely hot nights, especially pensioners who can't afford air conditioning.

Heat also causes droughts, flash floods and wildfires.

In 2021, the sky turned brown because of the smoke from wildfires right outside Athens. You couldn't breathe - it was post-apocalyptic.

Smoke blankets Athens after a wildfire in Varnavas, August, 2024. REUTERS/Elias Marcou

Smoke blankets Athens after a wildfire in Varnavas, August, 2024. REUTERS/Elias Marcou

Cities are heating up twice as fast as the global average because they're made from materials like concrete and asphalt that absorb heat.

Secondly, they lack vegetation, which helps with cooling, and thirdly, we're producing heat with cars and air conditioners.

The most vulnerable cities are around the equator.

They're already hot so even a small increase has a big impact. They're also often humid, and the combination of humidity and heat is very dangerous. And a lot of them, like Lagos and Jakarta, are growing very fast.

Air conditioning is not the panacea because of course it heats up the local environment and the planet, creating a vicious circle. So, we have to change the way we design and use our cities to make them cooler.

Introducing nature makes an enormous difference. Medellín in Colombia has created 30 green corridors and many green hubs. Singapore, Paris and Freetown are also radically bringing nature into the city. This can lower temperatures by 2-6 degrees.

A view of Gardens by The Bay, an urban park in Singapore, November 19, 2024. REUTERS/Edgar Su

A view of Gardens by The Bay, an urban park in Singapore, November 19, 2024. REUTERS/Edgar Su

In built-up cities like Athens, we've prioritised public space for private cars, so we have to change the way we think about that. We need to promote other types of mobility in our cities so we can dedicate more public space to green areas.

We also have to shade public areas. People still create pedestrian streets and squares without shade, which is insane. And finally, we have to bring water elements to urban design and open up passages to improve airflow.

New construction materials can also help like smart glass, which can block heat, and 'cool' paints for roofs. Some now reflect 80-90% of sunlight.

There's been a very big change in attitudes - three years ago nobody really talked about how dangerous heat is. But it's still not a priority for policy makers.

Extreme heat is now the deadliest climate-related hazard, but cities aren't prepared. The Brazilian COP presidency and UNEP (U.N. Environment Programme) are launching Beat the Heat to close that gap.

Over 100 cities have joined the call, and almost as many countries and partner organisations.

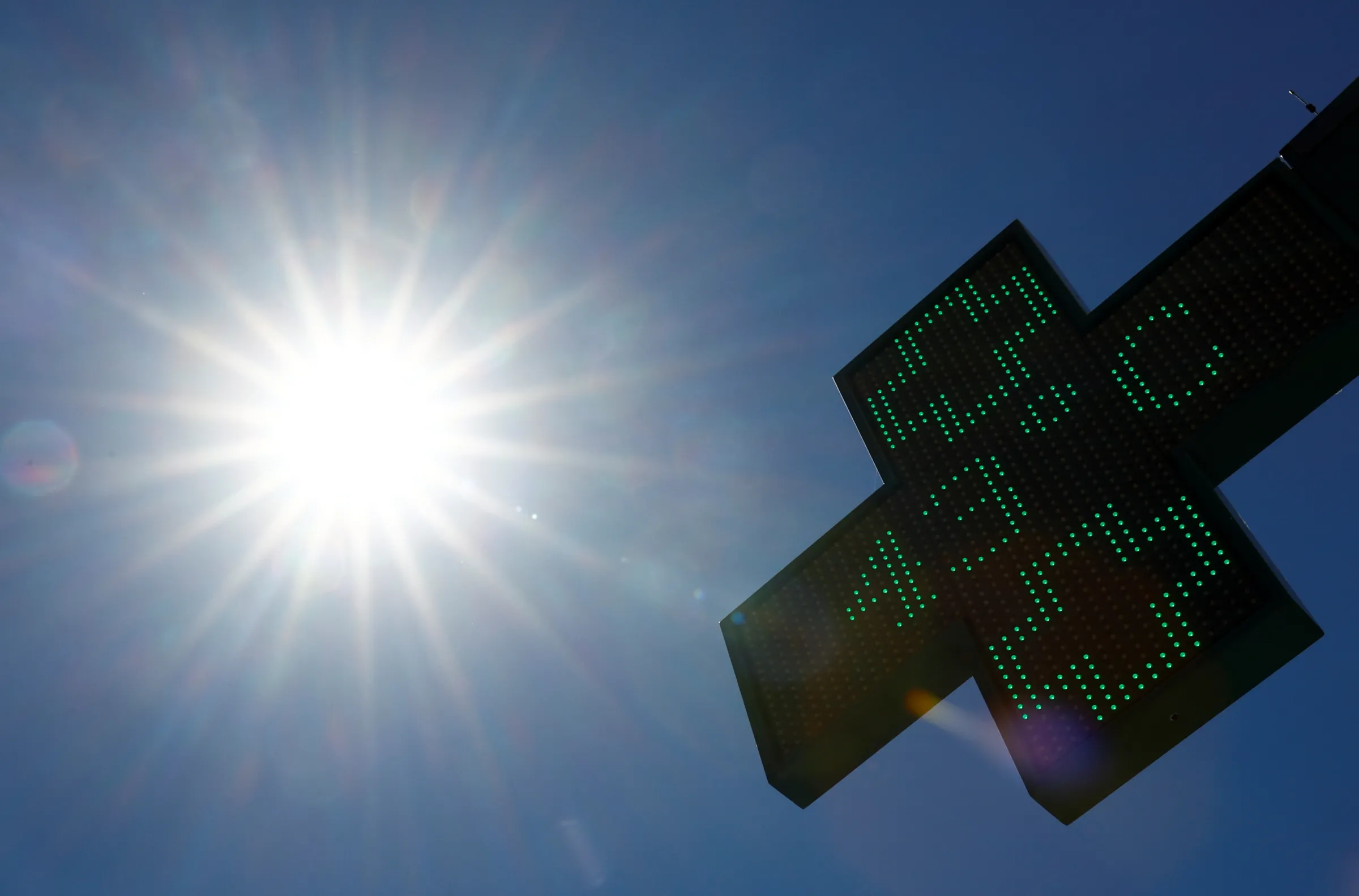

A pharmacy sign in Nantes shows the temperature as a heat wave hits France, July 13, 2022. REUTERS/Stephane Mahe

A pharmacy sign in Nantes shows the temperature as a heat wave hits France, July 13, 2022. REUTERS/Stephane Mahe

We will ask cities what they need to work on most urgently, and what help they want. This might be support with heat mapping or technical or financial assistance for specific projects.

Google and other partners are providing heat mapping and modelling tools. These can show where hotspots are and bring visibility to communities that otherwise might be overlooked.

Satellites and computational technologies can now give very high granularity of data on surface heat, down to almost one square metre. We can also calculate air temperatures.

With these datasets and AI (artificial intelligence), we can work out where to put trees and cool roofs and how to increase shading and improve air circulation for the best impact.

Ultimately, the goal is to make cities more liveable and to save lives. Cities are at the forefront of the climate war.

(Reporting by Emma Batha; Editing by Lyndsay Griffiths.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles