Reporter's notebook: Letting neurotechnology read my mind

Context report Avi Asher-Schapiro tries out the Emotiv Brain-Computer-Interface neurotech device. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jacob Templin

What’s the context?

For a privacy-obsessed reporter, testing brain-computer interfaces is a nerve-wracking and mind-expanding ordeal

- Devices that can decode brain waves are available commercially

- Lawmakers and scientists are trying to build guardrails

- Context making a film exploring the promises and pitfalls

LOS ANGELES - Last month, I flew to Colorado to have a neurologist attach a bunch of electrodes to my head and download my brain waves.

I am a privacy-conscious person. I browse the internet with a VPN, I use DuckDuckGo instead of Google, and I tend to use fake names and burner emails when I log into websites.

For the last few years, I have been writing about advances in consumer neurotechnology, and although I did not feel completely comfortable giving over my brainwaves, I needed to see how the technology worked for myself.

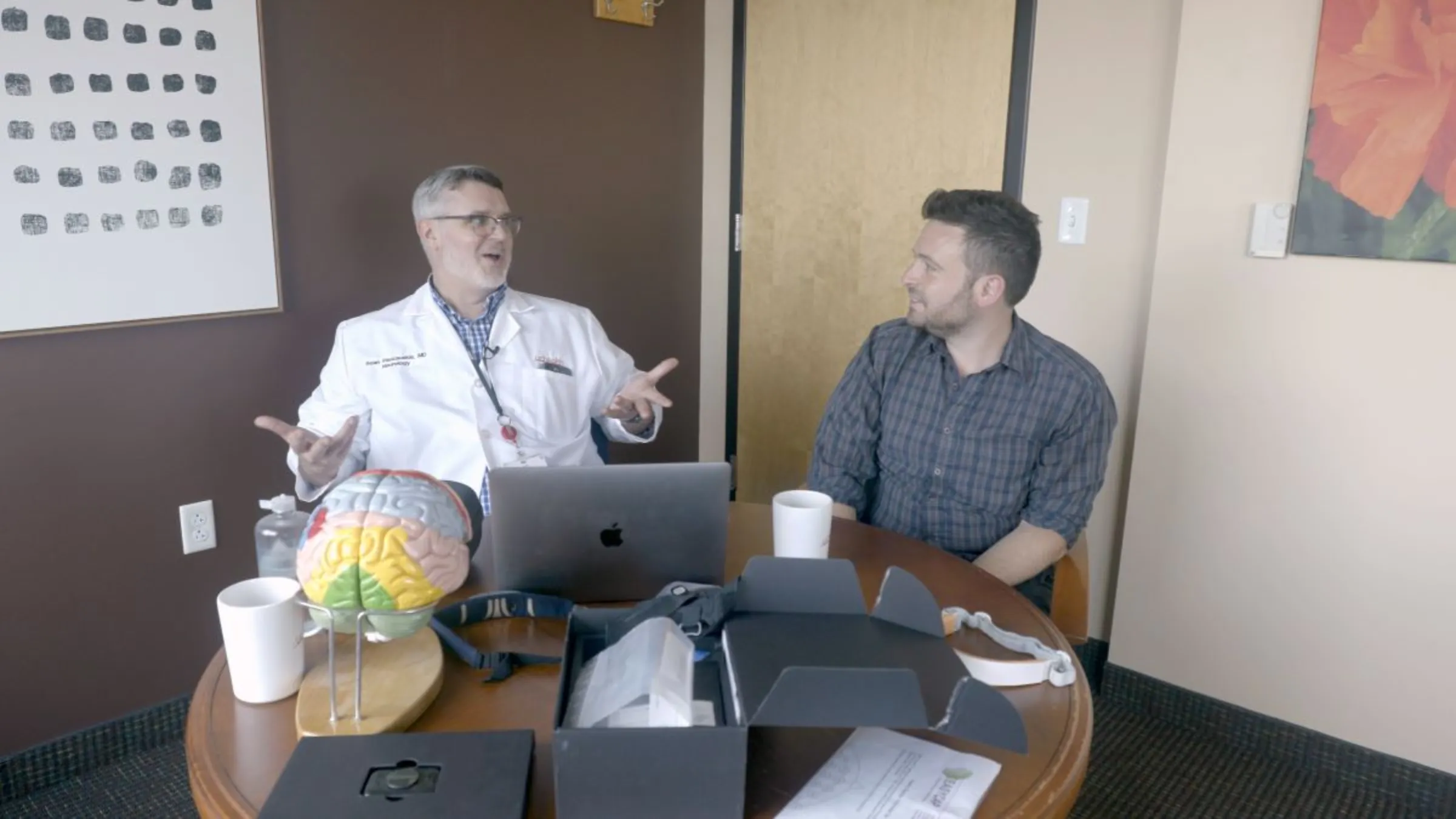

That's how I found myself in the offices of neurologist Sean Pauzauskie, watching him apply saline solution to an Emotiv Brain-Computer-Interface (BCI), so that its 14 nodes could get a strong signal through my skull.

We were filming a scene for an upcoming Context documentary looking at recent advances in neurotechnology and the inevitable ethical and policy questions.

The dial-up modem

The apparatus Pauzauskie affixed to my head can be purchased by anyone on the internet, even though, as Pauzauskie explained to me, the electroencephalogram (EEG) readings are medical grade, similar to what he would use in a hospital setting.

After a few minutes, I could use the device to control the facial expressions of an avatar on his screen. When I smiled, it smiled. When I winked, it winked.

It was an unsettling experience. Is privacy even possible in a world where a machine can look at your brainwaves and decipher your expressions?

The machine is not perfect. Sometimes it thought I was smiling when I wasn't.

"This is like the dial-up modem version of the internet - it's early, but it's here," said Pauzauskie, who helped lead an effort to make Colorado the first state to enact a law creating privacy rights for brain data in April.

To be clear, the number of things the interface could decipher about my thoughts was limited. Aside from my facial expressions, I could move a square cube up on the screen. But that was about it.

Still, scientists in Australia last year published a study showing that similar devices could extract actual words from your brain if the brain waves were run through powerful artificial intelligence systems that mapped the relationship between brain waves and certain words.

The medical grade headphones can capture and decipher the wearer's brainwaves. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Brandon Tauszik

The medical grade headphones can capture and decipher the wearer's brainwaves. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Brandon Tauszik

Splitting the atom

When we interviewed Rafael Yuste, a neuroscientist at Columbia University and founder of the Neurorights Foundation, he compared the significance of recent advances in neurotechnology to splitting the atom.

He has been traveling the world trying to get governments to recognize "neurorights" and regulate the technology before it gets out of control.

In April, Pazauski joined Yuste's organization as its medical director.

A week after my trip to Colorado, I met with neuroscientist Ramses Alcaide in Los Angeles, who showed me a prototype of brain-wave detecting smart headphones that his company Neurable is releasing later this year.

He envisions a world in which EEG-measuring devices are integrated into most - if not all - consumer technology.

"If you're listening to an audiobook, it could detect when you're not really paying attention, and it pauses," Alcaide told me, passing me a trial pair of the $699 headphones.

Neurable builds algorithms that boost brain signals from across the brain so that they can be read by all sorts of devices, headphones, helmets or earbuds.

With the headphones on, a line of a graph ticked up as I focused on numbers flashing on the screen. When I relaxed my mind, the line dipped.

Alcaide said the headphones are meant for workers looking to maximize their focus and avoid burnout. He pushed back on my concerns that such technology could lead to mind-reading or other dystopian scenarios.

"These are very high-level signals," he said of the EEG data that his headphones capture and analyze.

Figuring out if you’re smiling or focused from an EEG scan is easy, he said, but detecting your innermost thoughts and desires is difficult. What you are typing into a browser on your phone or your credit card history is much more revealing.

And devices that extract whole sentences or complex thoughts from the brain are too clunky to be commercially viable anytime soon, he said.

Sean Pauzauskie, medical director The Neurorights Foundation, discusses brainwave-reading tech with Context report Avi Asher-Schapiro in the U.S. state of Colorado on August 5, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jacob Templin

Sean Pauzauskie, medical director The Neurorights Foundation, discusses brainwave-reading tech with Context report Avi Asher-Schapiro in the U.S. state of Colorado on August 5, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jacob Templin

What's the limit?

I was still wondering if there were some hard barriers to the kind of data that could be decrypted from my brain waves, if the technology becomes better at capturing and deciphering EEG.

"What's the limit?" I asked Pauzauskie. "Well, theoretically," he paused, and said, "there is no limit."

Pauzauskie was not trying to scare me. He’s an enthusiast for the technology, using commercially available EEG machines to monitor patients' brains and treat them for strokes and epilepsy. He also uses EEG headbands on himself to meditate and monitor his sleep.

"It's a game changer," he told me.

Alcaide was first motivated to work on neurotechnology because he wanted to build high-tech prosthetics to help an uncle who had lost both legs in an accident.

He imagines a world in which brain data flows freely from headphones to researchers and doctors who could review it for early signs of Alzheimer's or other degenerative conditions - as long as they have the user's consent, he emphasized.

The day after Pauzauskie measured my brain waves, I drove to the Colorado State Capitol to talk to Kathy Kipp, a member of the legislature who Pauzauskie first approached about enshrining privacy for brain data into state law back in 2022.

"It's something everyone can agree on," she told me, pointing to the bipartisan support she garnered for her bill, which Governor Jared Polis signed into law in April.

The law adds neurological data to Colorado’s existing privacy law requiring companies to obtain consent to collect and transfer the data and providing consumers the right to request its deletion.

It is the first state to explicitly extend these protections, and experts are not sure exactly how it's going to pan out.

Technology industry groups pushed to have language clarifying that sensitive data protection applied to neural data collected for "identification purposes." And experts we spoke with disagreed if that meant that companies like Neurable would even be covered by it.

Still, the law has put neurotechnology on the radar of lawmakers and regulators across the country. We have been following closely as a similar bill winds its way through the legislature in California, a key laboratory for national tech policy.

(Reporting by Avi Asher-Schapiro; Editing by Ayla Jean Yackley.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Digital IDs

- Data rights