Buried in Somalia: A Filipino migrant fisher's death exposes abuse

What’s the context?

Seven years after Sam Dela Cruz died fishing far from home, his family seeks answers from an industry with few worker protections.

TUKA, Philippines/MANILA - After the body of 25-year-old Filipino fisherman Sam Dela Cruz was returned to his shipmates after his sudden death in Somalia, they carried his body, wrapped in a blanket, into the ship's freezer to take him home to his family.

One fisherman "got water and a cloth to clean Sam's face," said Gilbert, another Filipino on the ship who used a pseudonym due to concerns for his safety. "Then we all just cried."

Their mourning was cut short the next day when armed Somali officers arrived to take Dela Cruz's remains and bury him in a public cemetery in the port city of Bosaso, where their Chinese-flagged fishing vessel, the Han Rong 355, was docked in 2018.

"We need to hide your friend under the land," Gilbert recalled being told by the ship's security guard who had informed him that Dela Cruz had died of a heart attack at a hospital.

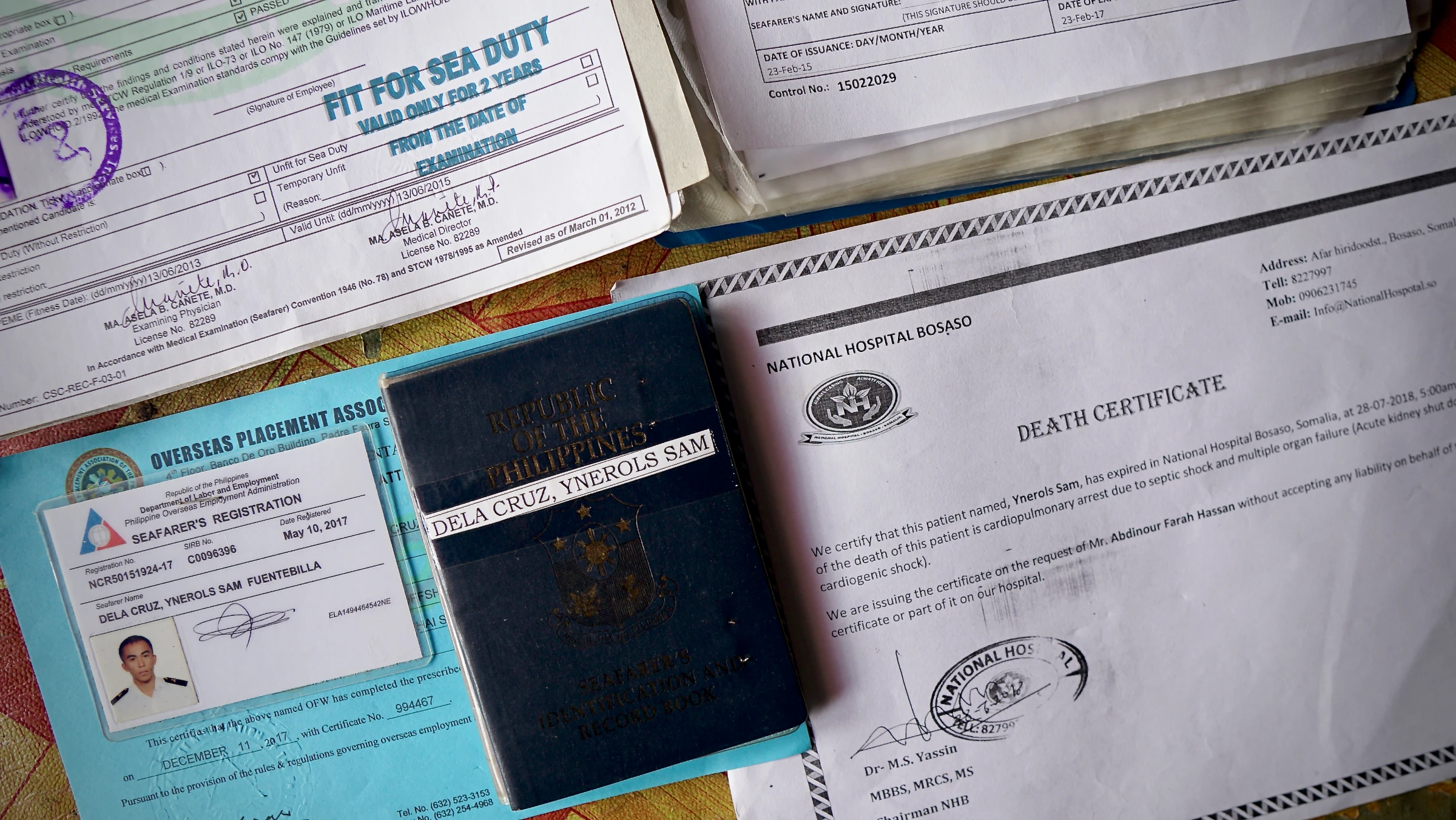

Sam Dela Cruz’s documents show that he died of cardiac arrest due to acute kidney failure in the early morning of July 28, 2018. Previous medical records certified that he was fit for sea duties. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Sam Dela Cruz’s documents show that he died of cardiac arrest due to acute kidney failure in the early morning of July 28, 2018. Previous medical records certified that he was fit for sea duties. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Dela Cruz was one of the 66,000 or more Filipinos deployed on foreign fishing vessels over the past decade, according to the Philippines' Department of Migrant Workers (DMW). Along with Indonesia and Vietnam, the Philippines is among the top countries of origin for migrant fishers.

Official data showed more than 40% of Filipino migrant fishers have had to be repatriated by the government when their contracts expire or they are subject to ship abandonment or mistreatment.

But deaths like Dela Cruz's are under-documented, and researchers said it is difficult to determine how many migrant fishers perish at sea every year.

Context spoke to witnesses, examined documents and interviewed Dela Cruz's family to investigate the circumstances that led to his death and burial.

His case shows the dangers fishers from the Philippines face in an industry that rights advocates say is poorly regulated and rife with abuse - including the risk of never returning home.

Go deeper: Life and loss at sea: international shipping’s seafarer abandonment problem

Sick at sea

Seven years after this death, Dela Cruz's parents are still waiting for his remains to be returned to their quiet farming village of Tuka in Sultan Kudarat province in the Philippines.

"I really cannot sleep, and I feel like I'm going crazy. I can't eat much, because my mind is still with Sam," his mother Roselyn said.

Sam Dela Cruz’s mother, Roselyn, blankly stares across the kitchen, which has become a usual habit in the years since her son’s demise. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Sam Dela Cruz’s mother, Roselyn, blankly stares across the kitchen, which has become a usual habit in the years since her son’s demise. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

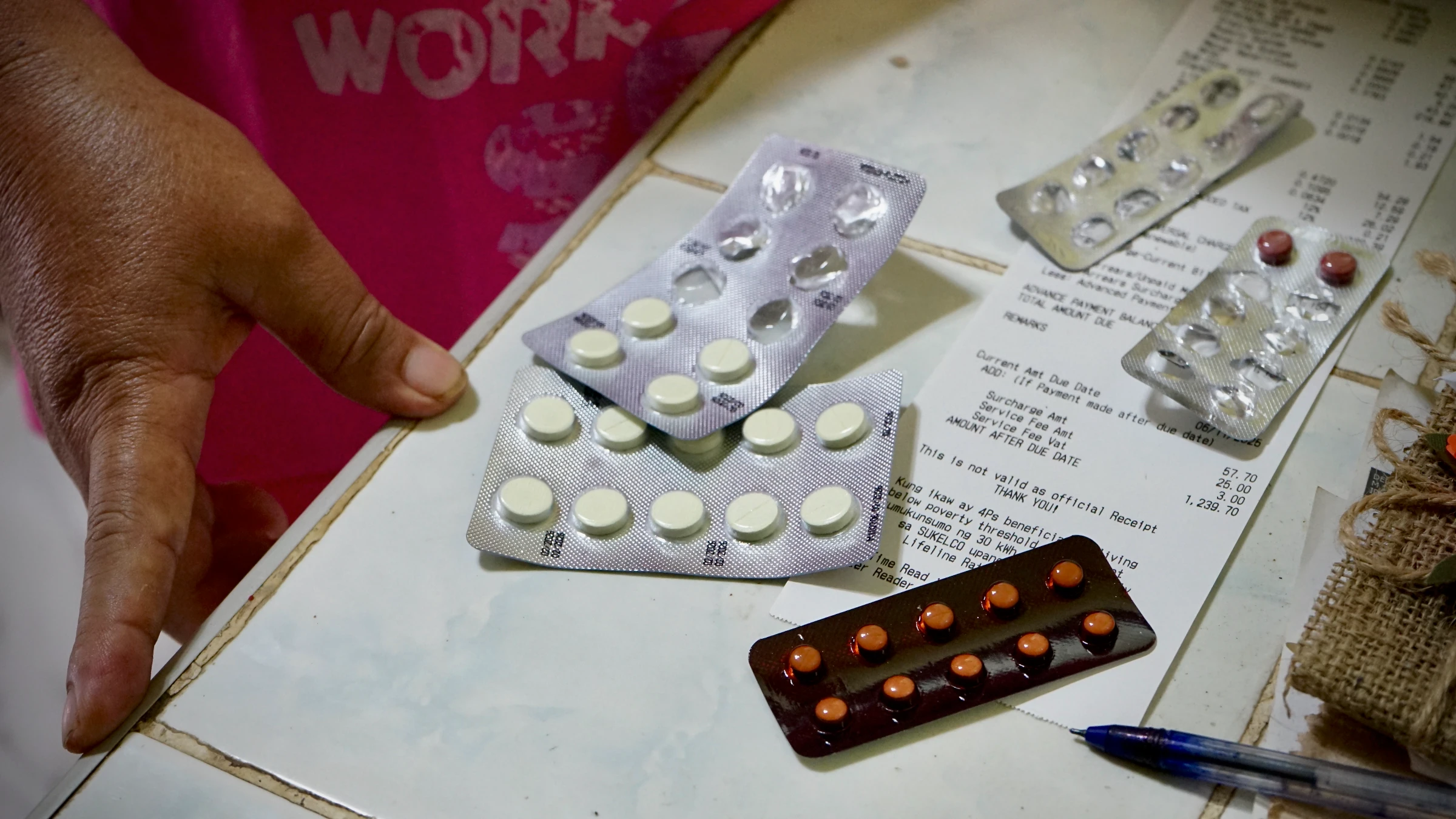

The family has spent much of the $35,000 in compensation paid by a Philippines recruitment agency on Roselyn's hospital visits and medication after her physical and mental health declined following her son's death.

Roselyn shared how her son had dreamed of becoming a seaman and travelled to the capital Manila in 2017 to apply for overseas work with the agency, GMM Global Maritime Manila.

Dela Cruz was instead offered a job fishing, which Gilbert said recruiters often sell as a stepping stone to more lucrative seaman positions.

On New Year's Day in 2018, Dela Cruz, Gilbert and seven other Filipino workers flew to Singapore, where the ship management services firm GMH Global Maritime Holding was based. The company quickly deployed them onto the Han Rong 355 to work alongside Chinese and Indonesian fishers.

Attempts to contact GMH Global Maritime were unsuccessful. A Singapore online business directory describes the company as "struck off" its registry, which can mean it has ceased operations or changed names.

Sam Dela Cruz’s mother, Roselyn, prepares the medication that she takes after her physical and mental health worsened since her son’s passing. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Sam Dela Cruz’s mother, Roselyn, prepares the medication that she takes after her physical and mental health worsened since her son’s passing. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Medical records from 2013 to 2017 showed Dela Cruz was healthy and certified fit for sea duty. But after reaching Somalia in June, he began limping and complained of pain in his stomach and thigh.

"I told him to talk to the captain, so he could have a check-up," said Gilbert. "But the (Chinese) captain responded through sign language, (telling him) just to jog because he lacked exercise."

A month later, Dela Cruz was rushed to the National Hospital Bosaso for treatment as the pain persisted.

He died on July 28, 2018, succumbing to cardiac arrest due to septic shock and multiple organ failure, hospital records said.

Hasty burial

Dela Cruz's family flew to Manila within days of receiving a call from GMM Manila saying he had died to discuss repatriation of the body, only to learn it was too late.

Somalia follows Islamic customs and buries the dead quickly. But other factors may have been at play in the hasty burial of Dela Cruz, who was Christian.

Gilbert said it took several appeals to convince GMM Manila to have Dela Cruz's body brought from the hospital to the ship.

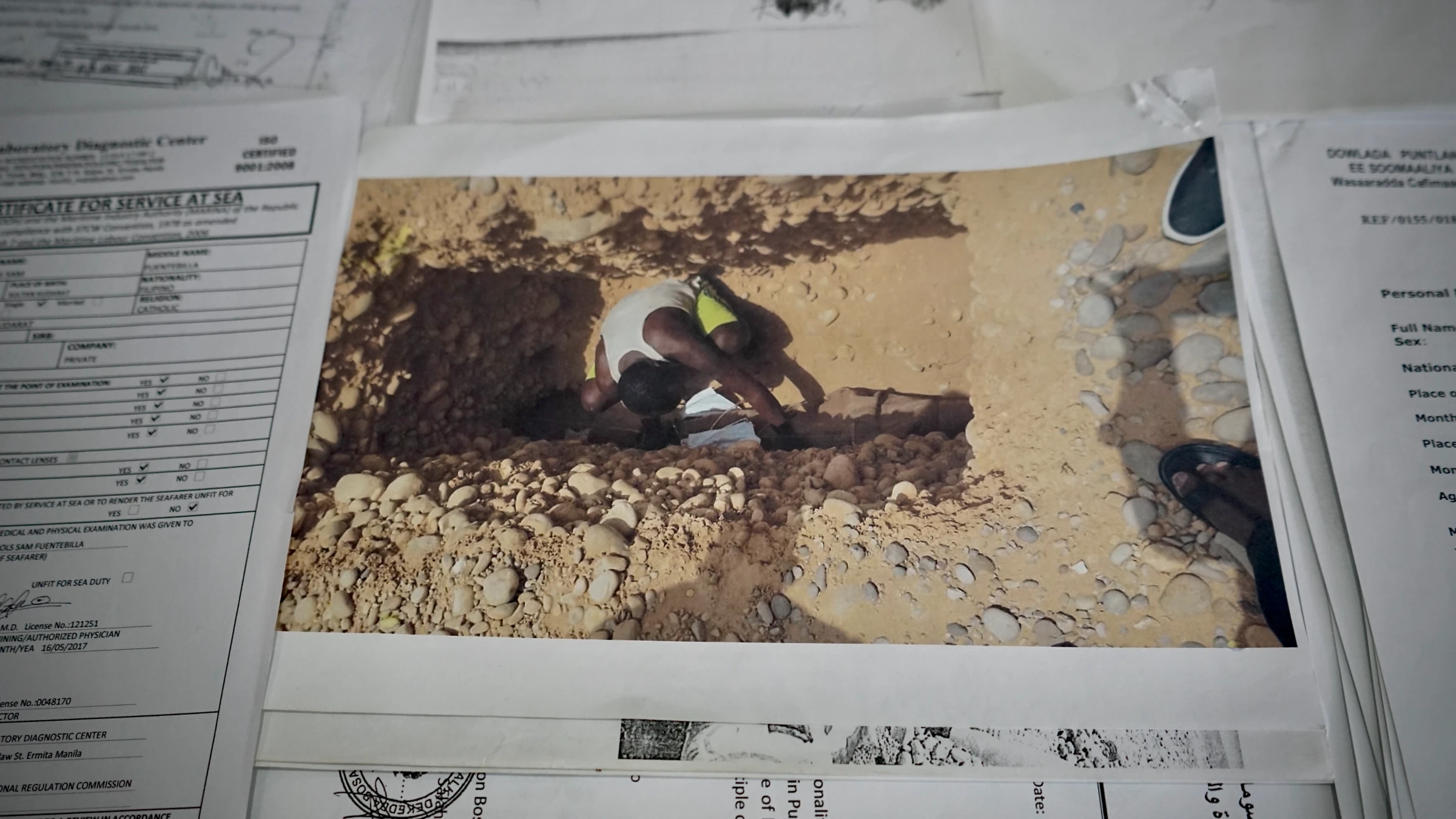

But a Han Rong 355 agent then filed a burial request with a Somali court the day after his death, and local officials in Bosaso buried Dela Cruz later that day, according to documents analysed by Context.

A burial confirmation photo relayed by a former fishing colleague shows Sam Dela Cruz being buried at a public graveyard in Somalia on July 29, 2018, one day after his death. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

A burial confirmation photo relayed by a former fishing colleague shows Sam Dela Cruz being buried at a public graveyard in Somalia on July 29, 2018, one day after his death. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Context was unable to determine the ownership structure of the Han Rong 355. In a report on the recruitment of migrant fishers, Greenpeace identified its owner as China-based Zhejiang Hai Rong Oceanic Fisheries Co., but e-mails seeking comment from Zhejiang were not answered.

It took GMM Manila three days to report Dela Cruz's death to the Philippine government, which may have delayed official efforts to claim the body.

"The repatriation of remains is a deeply humanitarian issue reflecting our shared respect for the deceased and their grieving family," said Robert Ferrer Jr., assistant secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs' Office of Migrant Workers Affairs.

"We pledge to keep them informed as developments occur and ask for understanding of the complexities involved," Ferrer told Context.

Sam Dela Cruz’s aunt, Judith, looks at her nephew’s death confirmation photo, in which he lies lifeless in a hospital bed in Somalia. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Sam Dela Cruz’s aunt, Judith, looks at her nephew’s death confirmation photo, in which he lies lifeless in a hospital bed in Somalia. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

The Philippine Embassy in Nairobi was tasked in July 2025 with reviving negotiations with Somali authorities to bring Dela Cruz's remains home. Earlier efforts by GMM Manila to exhume and repatriate Dela Cruz's body ended in 2019, according to documents.

GMM Manila did not respond to requests for comment.

But Marlon Martija, a former welfare officer at GMM Manila who handled Dela Cruz's case, answered questions over WhatsApp, saying the company understood the case had been resolved once the family signed a settlement agreement.

Go deeper: UN maritime chief links rise of dark fleet to worker abuses

'Nefarious operators'

Rights groups have found that companies operating fishing boats often fail to intervene quickly enough when a crew member falls ill.

Dominic Thomson, deputy director and project manager for Southeast Asia with the Britain-based human rights group Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), said burials on land or at sea have become practice by "nefarious operators" across the region.

"It's almost up to the discretion of the captain whether they go back to port or take a detour from the fishing grounds to make sure that a fisher can get home or get to a hospital in time," he said.

Shortly after Dela Cruz's death, Gilbert and the other Filipino fishers appealed to GMM Manila for help in their own repatriation, citing the trauma of witnessing their friend's death and poor working conditions on board the ship, including a lack of clean drinking water. It was to no avail.

A Chinese fisher on the ship died about a month after Dela Cruz's death, Gilbert said. He was buried beside Dela Cruz's grave in Somalia, documents showed.

Sam Dela Cruz’s mother, Roselyn, keeps her late son’s clothes. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Sam Dela Cruz’s mother, Roselyn, keeps her late son’s clothes. Sultan Kudarat, Philippines, June 4, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Raizza Bello

Then Gilbert and other crew members on the Han Rong 355 began showing similar symptoms to Dela Cruz's.

"I accepted that I will die there," Gilbert said.

But he survived the illness while the ship was docked for six months in Somalia - a place Gilbert was never told his ship would sail.

'Patchy jurisdictions'

Nante Maglangit, who had worked as a migrant fisherman, stood at a busy intersection near the National Library of the Philippines in Manila in May. It was his first visit to the area since winning a lawsuit against his employers in 2022.

"This building gave me nightmares," he said, pointing at the former office of the manning agency that had hired him in 2019.

Maglangit, now 35, sailed across the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean on different Chinese fishing vessels for two years - without adequate meals and potable water, nor timely or full payment of his salary.

He and his crewmates were abandoned in the open sea for nearly three months after their contract expired in 2021 when the COVID-19 pandemic prevented their boat from docking.

It would take until 2024 for Maglangit's recruiter and a China-based shipping company to pay him about $5,000 after a Philippine court found they had violated his contract.

Filipino fisherman Nante Maglangit poses for a photo after an interview, along Manila Bay in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

Filipino fisherman Nante Maglangit poses for a photo after an interview, along Manila Bay in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

Many of the Filipino workers recruited onto foreign fishing vessels come from remote areas and lack the know-how and resources to report exploitation and pursue lengthy legal proceedings, Maglangit said.

Rights defenders fear thousands of Filipino migrant fishers are trapped in abusive working conditions in an industry they describe as difficult to regulate since it operates under loose domestic and international laws.

Hussein Macarambom, national coordinator for the International Labour Organization's (ILO) Ship to Shore Rights Southeast Asia project, said "a mix of patchy or overlapping jurisdictions" in the fishing industry makes enforcing worker protections difficult.

Those jurisdictions include a fisher's home country, as well as the countries where he works, where the ship is registered, where fishing is carried out and where the port it docks at is located, he said.

A view of the documents of Filipino fishermen during an interview in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

A view of the documents of Filipino fishermen during an interview in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

"Each of these places has its own laws and policies about fishing, labour and immigration, which are not always consistent with international labour standards," Macarambom told Context.

Greater coordination between governments is needed to give fishermen the protections migrant workers on land are meant to have, including transparent recruitment, access to legal aid and stronger accountability mechanisms, he added.

Philippine authorities are only able to sanction local manning agencies found to engage in wrongdoing, while foreign shipowners and recruiters operating online from abroad are beyond their reach said Jerome Pampolina, the DMW's assistant secretary for sea-based overseas Filipino workers.

Only seven companies have faced disciplinary action for cases involving Filipino migrant fishers in the last 10 years, according to DMW information.

This list excludes Maglangit's local and foreign employers, even though the DMW suspended the recruiter's license in 2023 for charging seafarers placement fees - illegal under international law.

Environmental activists at Greenpeace and labour rights group Verité have published research showing that migrant fishers from the Philippines and elsewhere face illegal recruitment methods and the risk of forced labour.

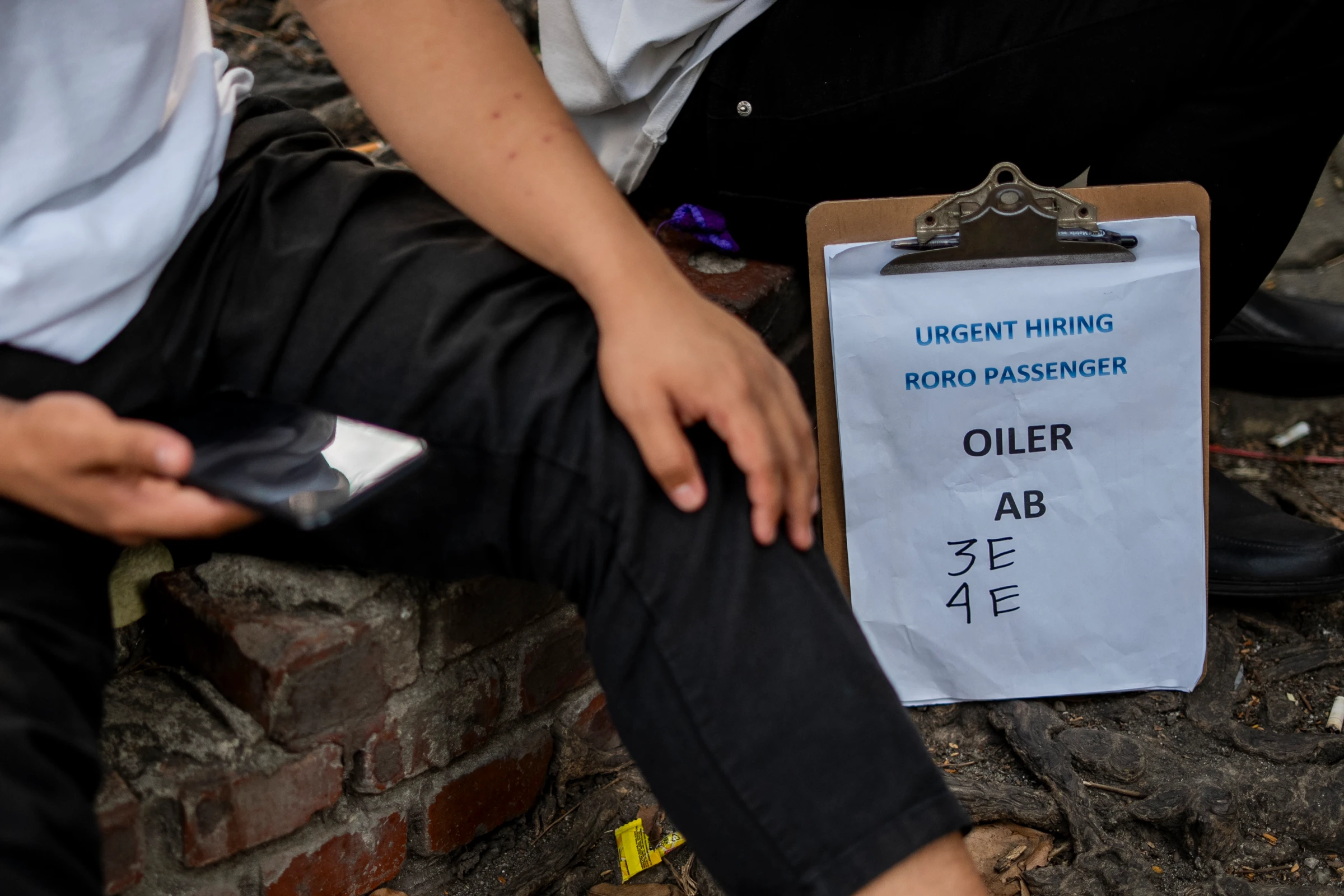

At the crossroads where Maglangit stood, young men could be seen outside of the offices of agencies that offer placement in maritime jobs.

A general view along Kalaw Ave. where seamen and fishermen are recruited, in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

A general view along Kalaw Ave. where seamen and fishermen are recruited, in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

Seafarers working on cargo ships also come to this district of Manila to find work, but fishers face different treatment, Maglangit said.

"People look down on us because we're paid way less than seamen on cargo ships. They see us as clueless people from the mountains who are not on the same level as them," he said.

Go deeper: How shipping's flags of convenience endanger seafarers

'Black market'

The EJF, which has interviewed more than 200 Filipino migrant fishers, compares recruitment practices in the Philippines and Indonesia to a "black market."

Informal brokers who live in the same villages as prospective fishers may go door-to-door to offer jobs on foreign fishing vessels, referring candidates to recruitment agencies in Manila and Jakarta. Once on board, workers are often denied their promised salaries, the EJF found.

Chinese fishing ships particularly have a poor reputation among workers, and fishers may end up on these boats against their will, the EJF said.

Instructional materials sold along Kalaw Ave. where seamen and fishermen are recruited, in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

Instructional materials sold along Kalaw Ave. where seamen and fishermen are recruited, in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

"It's akin to human trafficking," said Thomson. "It's a completely unregulated industry in a lot of aspects."

Four fishermen who worked on Chinese vessels told Context that they were forced to work for up to 18 hours a day fishing, freezing and packing their catch that included squid, tuna and mackerel. Maglangit said some of the haul from his boat wound up in China and Taiwan after being collected by another vessel.

Gilbert, who was never given a copy of his contract, only discovered that his vessel was in Somalia when his mobile phone picked up a signal in Bosaso.

Maglangit also worked on board vessels called the Han Rong. Like Gilbert, he described an illness in which his legs swelled, coupled with vomiting.

Gilbert said he and his shipmates on the Han Rong 355 were given "murky water" that "tasted like metal." Neither Gilbert nor Maglangit was diagnosed nor received medical attention.

It remains unclear what illness Dela Cruz and the other fishers suffered. A doctor shown Dela Cruz's hospital records said not enough information was available to determine what had caused his condition.

Go deeper: Dark Waters: Ships that hide crimes on the high seas

Gaps in protection

The global business of catching fish at sea is worth more than $140 billion, according to United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization.

An average of 6,000 Filipinos work on commercial foreign-flagged fishing vessels every year, according to the DMW.

That number does not include crew on unlicensed vessels that engage in illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, a dark industry that nets as much as $23.5 billion a year, according to Global Fishing Watch.

The plight of Filipino migrant fishers like Dela Cruz, Gilbert and Maglangit is part of a global crisis of forced labour and exploitation at sea, according to a 2024 report by the ILO.

As more companies sail longer distances to find fish, many increasingly rely on cheap labour from low-income nations like the Philippines, it said.

Because many commercial fishing operations are transnational, the ILO found that fishers often depend on the protection of the country where their vessel is registered.

A poster advertises seafaring jobs on Kalaw Avenue in Manila where seamen and fishermen are recruited, in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

A poster advertises seafaring jobs on Kalaw Avenue in Manila where seamen and fishermen are recruited, in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

However, ships may be based in states that either lack the capacity or the willingness to protect migrant fishers, the study noted.

Labour activists have joined migrant fishers to call on the Philippine government to pass a law to regulate local recruitment and to join the ILO's Work in Fishing Convention that sets basic standards for the industry, including safety, medical care and fair pay.

The treaty has been ratified by only 21 countries, and other conventions the Philippines has signed have failed to protect its migrant fishers.

While the Philippines is a signatory to the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC), which serves as a bill or rights for seafarers, the country classifies fishing vessels separately from cargo vessels, leaving fishers unprotected.

The MLC "does not cover fishers. So that's our problem," said Pampolina. "That's what makes fishers very vulnerable."

The only domestic protection for Filipino fishers is provided by the DMW, which was formed in 2022 to assist all workers at sea.

"If something happens on board a fishing vessel, we will provide the welfare protection and all the support, such as repatriation," said Pampolina.

Filipino fisherman Nante Maglangit poses for a photo after an interview, along Manila Bay in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

Filipino fisherman Nante Maglangit poses for a photo after an interview, along Manila Bay in Manila, Philippines, May 6, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Lisa Marie David

But that help came too late for Dela Cruz.

His parents have kept Dela Cruz's room as he left it, and a suitcase packed with clothes that his recruiter forced him to leave at the airport sits in another part of the house.

A large photograph of Dela Cruz wearing a uniform is hidden in plain sight in the living room, obscured by a torn and faded cloth with a Scooby Doo print.

"Our only wish is for Sam's bones to come home," his father Samson said. "So his mother can move on. She cannot have closure if her son isn't here."

Reporting: Raizza Bello and Mariejo Ramos

Editing: Ayla Jean Yackley and Amruta Byatnal

Photography: Raizza Bello and Lisa Marie David

Production: Amber Milne

Tags

- Migration

- Workers' rights