UN maritime chief links rise of dark fleet to worker abuses

A cargo ship is seen at the North Sea from the beach of Dishoek, Netherlands, July 19, 2018. REUTERS/ Kai Pfaffenbach

What’s the context?

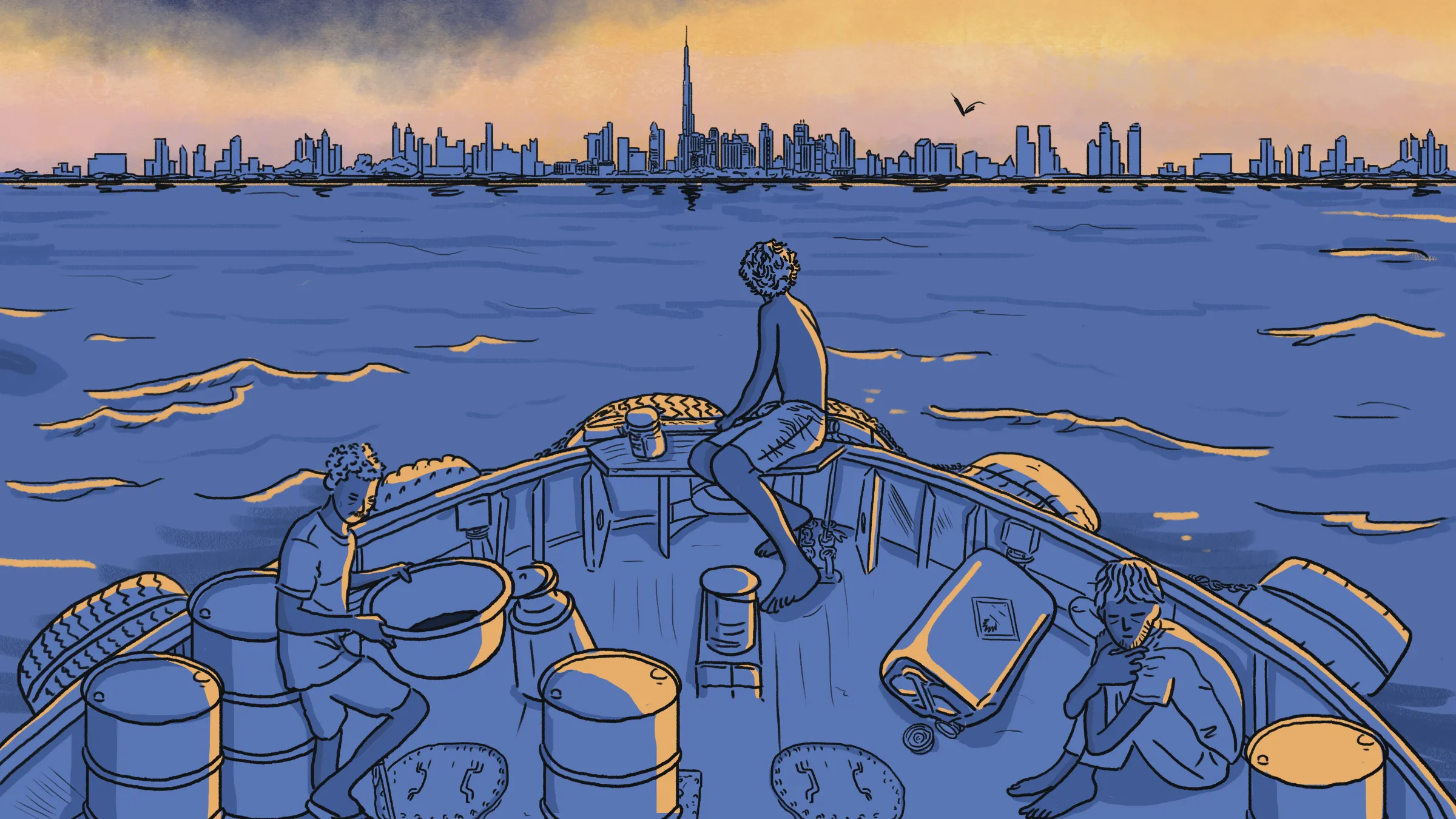

Seafarers face rising threats as shadow fleets and weak oversight of the industry endanger the backbone of global trade.

NICE, France - The head of the United Nations' maritime agency warned of a disturbing rise in the criminalisation of seafarers, driven by geopolitical tensions and a surge in substandard shipping practices linked to the so-called dark fleet operating outside international norms.

Conflicts across the world that disrupt trade, growing operational costs and regulatory weaknesses have left thousands of seafarers in a 1.8 million person-strong workforce vulnerable.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is "very concerned" about worsening conditions for workers, its secretary-general, Arsenio Dominguez, told Context.

Governments must do more to ensure fair treatment and due process for seafarers caught in the growing web of unregulated shipping practices, he said.

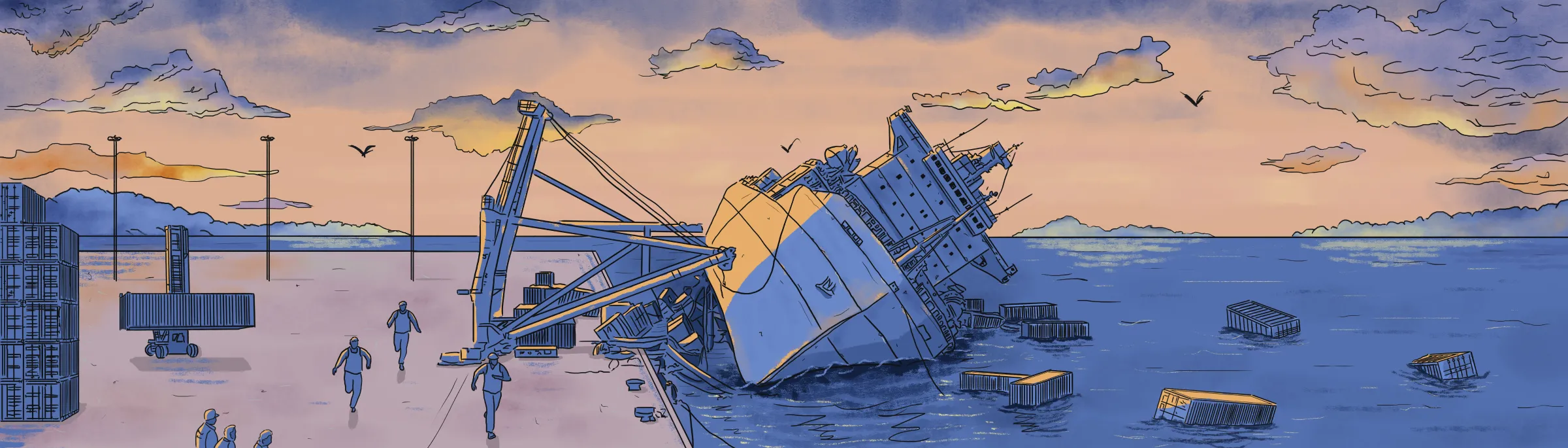

"We're seeing an increase in the abandonment and criminalisation of seafarers," Dominguez said, pointing to the expansion of shadow fleets, made up of vessels that obscure their ownership and movements to bypass sanctions and oversight, often operating beyond the law.

The dark fleet routinely transports illicit cargo and sanctioned products, such as Iranian and Russian petroleum, flouts regulatory rules and employs unfair working practices, such as forced labour, according to industry experts.

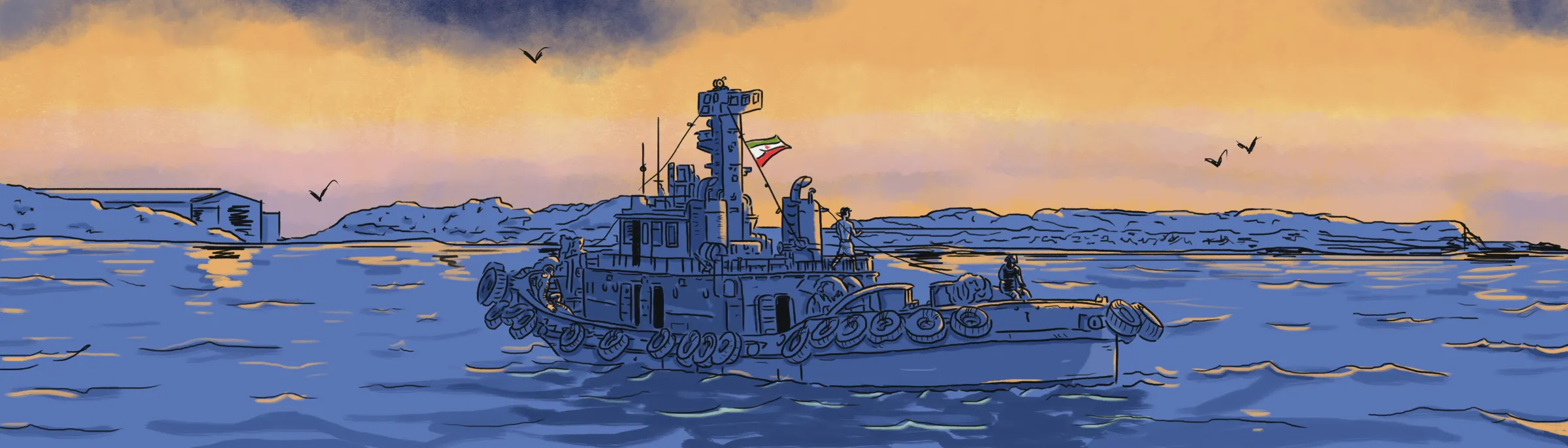

Shipping analysts track between 1,300 and 1,400 vessels operating in the global shadow fleet, and about half are crude oil tankers.

"These ships are putting seafarers at risk. Substandard shipping and ships that do not comply with the IMO regulations should not be operating," Dominguez said.

He confirmed that the IMO is now intervening in cases of seafarer abandonment, using the organisation's diplomatic leverage to pressure governments and flag states to uphold international standards.

"Whenever there's a case, I reach out to the member states and the flag states, and I work closely with organisations like the ITF to gather information and follow up," he said, referring to the International Transport Workers' Federation, which defends seafarers' rights.

The IMO has recently adopted new guidelines on the treatment of seafarers facing criminal charges for working on board vessels found to be carrying illicit goods, despite having no control over cargo or routes. It is also reviewing its regulations to address seafarer fatigue, violence and harassment at sea.

Yet the IMO's hands are tied when it comes to enforcement.

"It is not an intention of the IMO to engage or try to trespass into the judicial process of the countries. But I do ask for every single country to treat seafarers rightly, to provide them with due process," said Dominguez.

Rights crisis

Ship abandonments, in which seafarers are left unpaid, often without food or repatriation, after the owner walks away from a vessel, more than doubled in 2024, according to the ITF.

The consequences can be dire. Crews may be left stranded for months, detained without charge or denied medical care.

Many of these vessels are linked to the sanctioned oil trade. The IMO does not enforce sanctions, but instead seeks basic standards for safety, environmental protection and seafarer welfare.

Owners sometimes register their ships under flags of convenience in countries with lax regulations and tax loopholes, and Dominguez acknowledged that boats flying certain flags routinely appear in databases on abandonment and violations.

Last year, 90% of abandoned seafarers were working on vessels sailing under flags of convenience, the ITF said.

"We maintain statistics, and when patterns emerge, my first step is to start having the conversations" with flag states, said Dominguez.

This softer approach, Dominguez argued, is more sustainable. "Our job is to help build their capacity while ensuring they uphold their obligations."

Dominguez is working to sign more countries onto the International Labour Organization's Maritime Labour Convention, which sets minimum standards for seafarers. Several Middle Eastern countries and the United States have yet to ratify the agreement.

The proliferation of small ship-management companies has further complicated the picture. But expanding regulations should avoid creating rules that stifle the industry and cannot be realistically implemented, Dominguez said.

"We need to pace ourselves to maintain the quality of regulations and ensure they're actually enforced," he said. "And if we're really serious about attracting the new generations to seafaring, we need to start by actually treating better and keeping the seafarers right now."

(Reporting by Katie McQue; Editing by Ayla Jean Yackley)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Workers' rights