Don’t hold gender hostage – champions and blockers at COP30

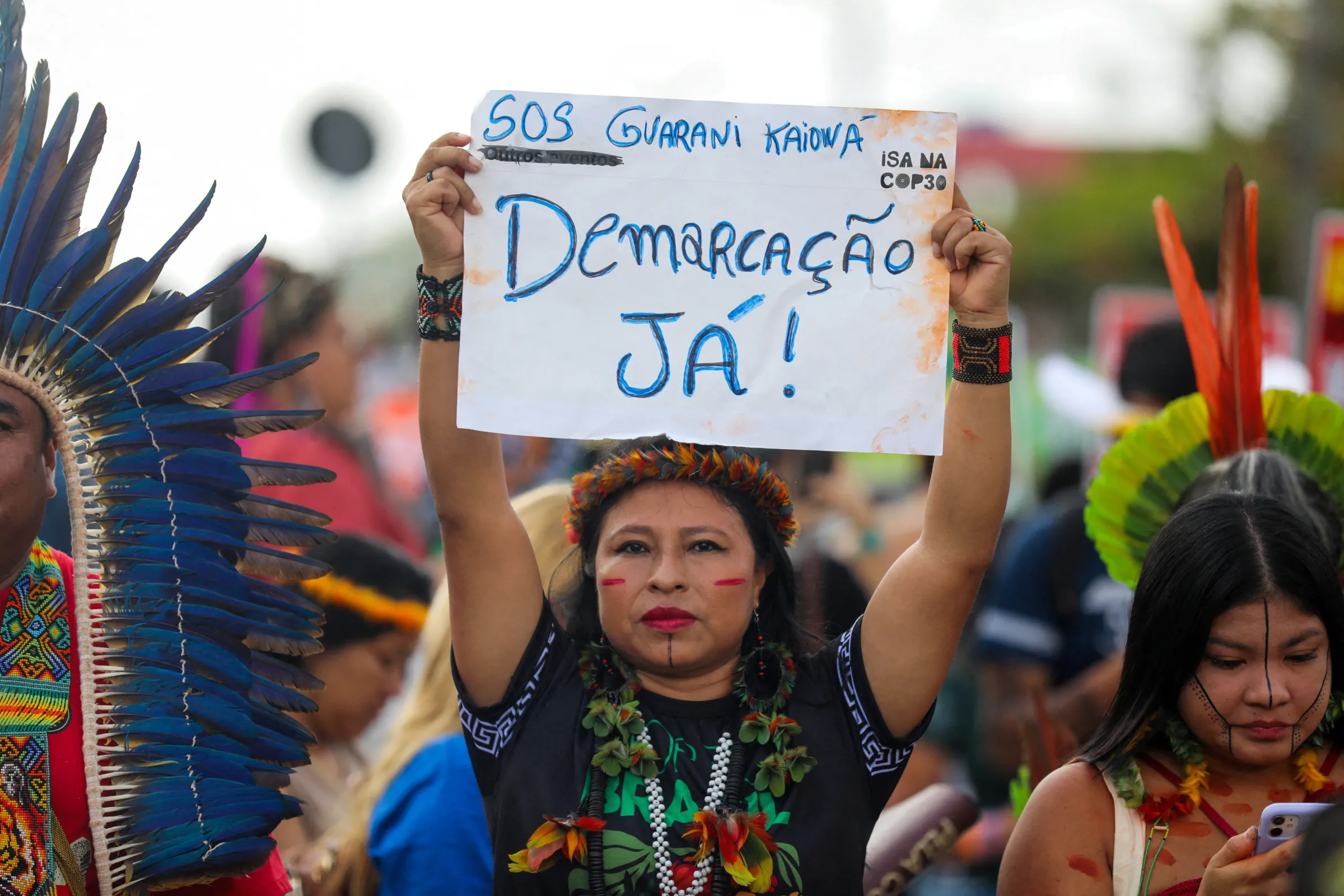

An indigenous woman holds a sign reading: "Demarcation now!", during a protest to call for climate justice and territorial protection during the U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP30), in Belem, Brazil, November 17, 2025. REUTERS/Anderson Coelho

Gender equality is being sidelined at the climate summit - here's who's defending it, who's dismantling it, and what's at stake

By Donya Khosravi and Amy Cano Prentice, researchers on climate and sustainability at ODI Global, a global affairs think tank.

It’s late in the Brazilian port city of Belém. Delegates at the COP30 climate summit huddle around screens. The air is heavy with caffeine and fatigue. On draft decision texts, one word keeps reappearing in square brackets – gender.

At the U.N. talks, brackets are bad news. They mean countries can’t agree. The words inside them are on the chopping block – debated, deferred, or quietly deleted when time runs out. And too often, real commitments to support gender equality don’t make it out alive. Gender is treated as a side issue, rather than the backbone of equitable climate action.

What’s at stake?

The climate crisis is not hitting evenly; it multiplies risks and magnifies inequalities. Migrant women and girls in informal settlements face more violence and less access to services, including sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). Gender-based violence (GBV) is rising in settlements for people displaced by climate hazards. Indigenous women and girls have limited access to services and shoulder unpaid care work. Girls and LGBTQ+ youth experience higher rates of school dropout when extreme weather events hit.

Systemic inequalities come together so that women, girls, LGBTQ+ people and gender-diverse people are less likely to realise their basic human rights. When negotiators bracket the word ‘gender’, they’re really bracketing people’s lives.

The politics behind the brackets

The U.N. climate convention is one of the few global forums where every country has a voice and a paper trail. Each year Parties file written submissions on what they think should make it into the final decisions. When you track the deliberations against the outcomes in previous years, a clear pattern on gender emerges.

The champions. The European Union (EU) and the Alliance of Small Island States are familiar champions, often joined by the Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean and the Least Developed Countries Group. New champions are also emerging. Under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil has become an advocate for gender equality.

What are the champions calling for? Strong, clear commitments linking gender equality to climate action that are timebound, supported and crucially, those commitments consider everyone: men, women, boys, girls and structurally marginalised groups such as LGBTQ+ people,

Indigenous people or people with disabilities.

The blockers. It’s trickier to identify blockers because they rarely leave a written trail. In the room, we see consistent pushback from countries and blocs omitting gender from their written submissions.

What are the blockers proposing? Attempts to water down agreed terms – changing ‘gender’ to ‘sex,’ and dropping ‘gender mainstreaming,’ ‘intersectionality’ and ‘diversity’ altogether. These sound like minor edits, but they weaken accountability, permit the continued exclusion and marginalisation of large groups of people, and challenge the idea of gender equality as a norm or even an aspiration.

When ‘gender’ is replaced by ‘sex’, it unravels years of progress on gender equality and inclusive climate policy. ‘Gender equality’ looks at how power works in society. ‘Sex’ refers to biological categories, which is far too limited. When terms like ‘sex’ or ‘women’ are used in outcome texts, a lot of people get left out.

Inside the negotiation room

Fast-forward to Belém, where Parties must agree the new Gender Action Plan (GAP) to govern gender-related activities within the U.N. climate regime for the next nine years. The Friday deadline was missed – leaving gender once again held hostage.

Saudi Arabia, Russia and Iran said the text contained “controversial elements” such as GBV, care work, and SRHR. Saudi Arabia argued the text didn’t respect national circumstances, despite being based on previously agreed language. The specificity of SRHR was watered down to ‘health’ by the Holy See, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Paraguay, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Russia preferred ‘equitable’ to ‘equal participation’, and Iran preferred ‘balanced’ to ‘equal’.

Argentina and Paraguay added a footnote defining gender as ‘male and female sexes’, after which Iran and the Holy See requested footnotes interpreting gender as biological sex, citing national laws and family values.

Eager to have a new plan, almost all other Parties urged flexibility – with familiar champions resisting attempts to water down the language and emphasizing that the GAP should be progressive and ambitious.

What we’re seeing at COP30 is not new. But now we’re laying bare the actors and tactics behind the backlash, and there are champions ready to push back.

Gender justice in the climate negotiations isn’t optional. Negotiators in Belém have opportunities this week to demonstrate their commitment to women and girls in all their diversity. It’s time to set gender free – free from brackets, from being treated as negotiable, and from the politics that keep holding it back.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- Gender equity

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5