What’s the context?

Seafarer abandonment cases have reached unprecedented levels in 2025, with a 30% increase compared with the same period in 2024.

NEW YORK - Every time a bomb exploded nearby when Satya Dev Rahul was stranded on board a ship in Yemen, the young seafarer feared for his life.

For nine months in 2024, he was trapped on the M.V. Captain Tarek, anchored in Hodeidah Port, while Yemen was at war and subjected to regular bombing raids.

As explosions lit up the sky, he could see terror on the faces of his colleagues. All of them had signed on as seafarers a year earlier, but none had been paid - a pattern of exploitation in the shipping industry that they were unaware of.

Months before, their employer, Sata Chartering Shipping and Co, had stopped communicating with them and abandoned the vessel, leaving the crew members to fend for themselves.

“There were blasts left and right, and we were in between. The ship would vibrate. We felt these were our last days,” Rahul, who was 31 at the time, told Context.

This was his first seafaring job after he completed a masters degree in business administration and obtained a maritime Certificate of Competency.

Eight Indian seafarers and eight seafarers from Syria worked aboard the M.V. Captain Tarek and could neither escape nor sail away. The captain had given their passports and logbooks to port authorities, effectively trapping them on board.

The crew was surviving on meagre rations of one daily meal of instant noodles cooked over a wood fire. They slept on the open deck, as the ship had no diesel to power its generator and without air conditioning, the cabins were unbearably hot. There was no fresh water on board, and to bathe, they would climb overboard into the sea.

“I had a full body allergy and was itching all over,” said Rahul, who is from Ghaziabad, near New Delhi.

For Rahul, the realisation that he and his colleagues had been abandoned was gradual. Contact between the ship owner and captain had grown less regular before stopping altogether.

The crew had not been paid for seven months. The cook stopped making meals for the crew, and the Syrian seafarers stopped working. Rahul quietly panicked.

“When all such things start happening, we realised nobody was there to take care of us,” he said. “And it was a war zone.”

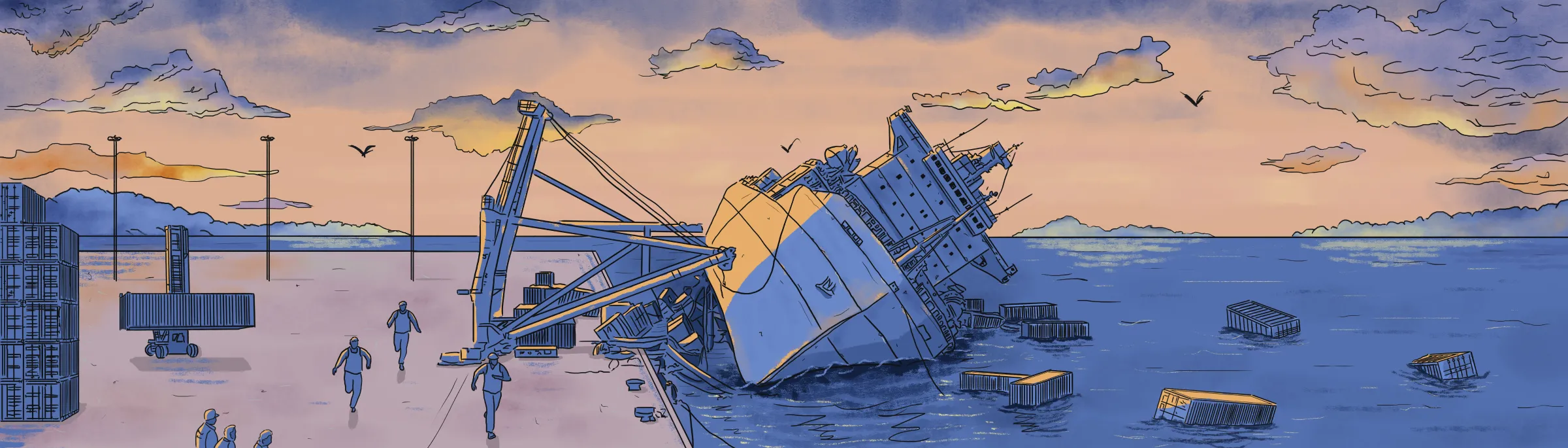

A seafarer covers his ears from the sound of explosions overhead in this illustration photo. When bombs exploded around stranded ships in warzones such as Yemen, seafarers like Rahul feared for their lives. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

A seafarer covers his ears from the sound of explosions overhead in this illustration photo. When bombs exploded around stranded ships in warzones such as Yemen, seafarers like Rahul feared for their lives. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

“We take all allegations related to seafarer welfare seriously and reiterate our commitment to upholding international maritime labor standards in all operations under our management,” said Capt. M. Hammoud, Sata Chartering’s International Safety Manager in an emailed statement to Context.

Sata Chartering is no longer associated with the vessel MV Captain Tarek, Hammoud added. He did not respond to follow-up questions about when the company ceased managing the vessel.

Yemen, which has been engulfed in a regional conflict with a coalition of Middle Eastern and African countries led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates since 2014, is a hot spot for abandoned vessels.

In 2024, the Houthi-controlled Hodeidah Port was subjected as well to bombing raids by Israeli forces, which Human Rights Watch condemned as “unlawful indiscriminate" attacks on civilians and a possible war crime.

Seafarer abandonment cases have reached unprecedented levels in 2025, with more than 2,280 mariners stranded aboard 222 vessels, marking a 30% increase compared with the same period in 2024.

This surge has resulted in $13.1 million in unpaid wages between January and July this year, the ITF said.

Soaring operational costs, unpredictable freight rates, mounting debts and lax regulatory oversight are issues driving abandonments.

Ship owners may opt to cut ties rather than pay wages, cover repatriation or maintain aging vessels.

The International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) defines seafarer abandonment as a situation in which a ship owner fails to cover a crew's wages, repatriation or basic needs, leaving them stranded aboard a vessel or in a foreign port.

Leaving an abandoned ship is difficult. Many seafarers have their passports and identification documents confiscated by their employer, and port or visa restrictions often prevent them from going ashore. They may choose to remain aboard in hopes that they will eventually be paid.

Context interviewed 11 seafarers abandoned by their employers and left drifting at sea or stranded in ports in this final instalment of an investigative series uncovering exploitation in the shipping industry.

Go Deeper: Dark Waters: Ships that hide crimes on the high seas

Gifts and threats

Almost 10% of the world’s seafarers hail from India, the third highest supplying nation behind China and the Philippines.

In India, irregular recruitment in the maritime sector is widespread, creating risks for seafarers. Sometimes agents work with companies intent on cutting costs and maximizing profits at the expense of the crew’s rights and welfare.

Even licensed recruitment agents, who are supposed to hold a valid Recruitment and Placement of Seafarers License (RPSL) from the government's Directorate of Shipping (DG Shipping) and follow fair labour practices, commonly break the rules.

They are supposed to ensure seafarers are paid their agreed salaries and not charged fees to secure employment, but in practise, recruitment fees and misleading promises about salaries or job destinations are widespread.

Rahul’s agent was licensed, yet he was required to pay $3,000 for the job and purchase a $1,000 Apple Watch “as a gift for the captain’s son,” he said.

The gift request sounded alarm bells at the time, but Rahul needed the work.

“Paying money for a job is normal here. But if they demand anything else, that is not good,” he said.

A seafarer holds an Apple watch in this illustration photo. Seafarers often need to pay to get jobs on ships, and also buy gifts, such as the $1000 Apple watch that Rahul bought for the captain's son. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

A seafarer holds an Apple watch in this illustration photo. Seafarers often need to pay to get jobs on ships, and also buy gifts, such as the $1000 Apple watch that Rahul bought for the captain's son. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Other rookie seafarers employed on the vessel had been made to pay even more, up to $4,500, he said.

Seafarers tend not to disclose what happens with recruitment agents who may threaten them over raising any alarm about their treatment.

“For family security reasons, nobody speaks about this,” Rahul said.

“There are really cases of slavery, not only severe exploitation. There are cases where seafarers are intentionally kept onboard for 10, 11 months without pay," said Mohamed Arrachedi, the ITF’s director for the Middle East and Iran.

“That’s slavery.”

One agent involved in recruiting the seafarers joined Rahul’s ship, taking a role as a crew member to keep them in line. When Rahul asked when they would get paid, the agent threatened to have him removed from the ship.

One of Rahul’s colleagues was subjected to so much violence from the agent he tried to jump overboard. When a hungry crew member on night watch attempted to make himself a snack, he was repeatedly beaten.

The intimidation became almost constant.

“He would say to us ‘You are here, but your family is alone in India," said Rahul.

No international treaty

Each commercial vessel must be registered with a country’s flag so that they have a legal nationality that determines the laws they must follow and the protections they receive at sea.

In 2024, nearly 90% of abandoned seafarers were stranded aboard ships flying ‘flags of convenience,’ a designation linked to nations with weak oversight and lax enforcement of shipping laws.

“Flags of convenience states are really just tax-saving registries. They don’t have the ability to investigate what goes on the ships,” said Cormac McGarry, director, maritime intelligence and security services, at Control Risks, a global risk and strategic consulting firm.

Ship owners may opt for a flag of convenience to bypass safety standards that may be required in their home country, avoid taxes and skirt laws that protect seafarers’ labour conditions and wages.

“These flags do not have any proper regulations. They are just there to make money,” said Chirag Bahri, operations manager at the International Seafarers' Welfare & Assistance Network (ISWAN), a non-profit that supports maritime workers in distress.

“These bad owners register their ships with them to get free from issues that arise,” he said.

Seafarers hold their passports in this illustration. People from India, Philippines and China make up the most number of seafarers. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Seafarers hold their passports in this illustration. People from India, Philippines and China make up the most number of seafarers. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Each year, the Paris Memorandum of Understanding (Paris MoU) – an administrative agreement among twenty-seven Maritime Authorities – issues a list grading flag states on their performance.

The least troublesome states are graded white, the riskiest are black and those that fall in between are grey.

Nations landing on the blacklist include Tanzania, Comoros, Palau, Vietnam, Ukraine and Algeria. Panama — one of the world’s most sought-after flag registries, known for its streamlined online registration, low-cost labour policies and tax-free incentives for foreign ship owners — is on the grey list.

There is no international treaty to regulate the black-listed flags. Some are tiny island nations that issue registries to vessels but have no control or regulatory mechanisms whatsoever.

Sometimes, should a ship owner cease paying for its flag, the flag state withdraws the registry, washing its hands of abandoned ships and seafarers in distress.

“The flags run away,” Bahri said.

Under the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC), an international treaty established by the International Labour Organization (ILO) to safeguard seafarers' rights, ship owners bear the ultimate responsibility for covering repatriation costs, unpaid wages, essential needs and medical care.

But when ship owners abandon their obligations, the burden shifts. Flag states, port authorities and recruitment agencies in the seafarers' home countries become responsible for their welfare.

But port authorities in some countries are ineffective due to a lack of clear lines of responsibility, political will or resources.

Go Deeper: How shipping's flags of convenience endanger seafarers

Expectations and sanctions

For nine months in 2021 and 2022, Nihal Sharma was forced to stay aboard an aged ship named Farvar in Genaveh Port, Iran. He was 26 and had recently graduated with a computer science degree.

The ship for three months had sailed back and forth to Kuwait, transporting camel feed and construction materials. Then the ship owner went out of business due to a loss of contracts.

The vessel was left anchored in Genaveh Port with only Sharma and another Indian seafarer on board. The boat had little fuel left, and the shipmates conserved use of the generator to power the air conditioning. They were also close to starving.

The ship owner kept tabs on them from shore, making it impossible to leave. He would bring scant rations of eggs, some tomatoes and onions, dried beans and peas every week or so. They were forced to beg for food from other ships that sailed into the port. The water supplied by the port made their throats hurt.

“I am calling him daily, messaging him. Please give me my salary,” said Sharma. “I told him I have to give some money to my father, and he is not responding. Sometimes bad thoughts also come into my mind. Sometimes, I think I will do suicide.”

Sharma had paid more than $4,600 for his seafaring job. In India, the recruitment agent promised him a salary of $550 per month. When he arrived in Iran, his employer told him the salary was actually $200. After the first two months, the payments stopped.

“Everybody is cheating, everybody takes advantage of us,” he said.

Mohamed Arrachedi, the ITF’s director for the Middle East and Iran, gets hundreds of WhatsApp messages every day from stranded seafarers asking for help. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Mohamed Arrachedi, the ITF’s director for the Middle East and Iran, gets hundreds of WhatsApp messages every day from stranded seafarers asking for help. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Arrachedi, from the ITF, is used to carrying two phones with him. One constantly flickers with WhatsApp messages that come by the hundreds each day and throughout the night. Seafarers, usually very young and inexperienced, stuck in impossible situations around the Middle East, are begging for his help.

The burden is great for Arrachedi, an affable middle-aged Moroccan man who is constantly travelling from his home in Bilbao, Spain, for his work.

One of his toughest tasks is managing the expectations of the desperate seafarers and their families, he said. It is difficult to extract them and fly them to safety, especially in the Middle East, where rescues can be hampered by red tape, visa requirements, sanctions, conflict and uncooperative governments.

Often, by the time seafarers reach out for help, their situations have deteriorated to dire, he said.

“We have seafarers who come to us because they have no food,” Arrachedi told Context.

At the time of this interview in March, Arrachedi’s team was providing assistance to abandoned vessels that included one in a Sudanese port, where the Russian and Indian crew members had not been paid for 18 months. To get them home, the ITF needed immigration passes on their behalf and a lawyer to allow them to leave the country. They also needed airfare.

Sometimes, the only way to pay the crew is to sell the ship and give them the proceeds, Arrachedi said.

But the crew cannot get their money if they have already left, and if international sanctions are involved, they may not be eligible to get the money at all.

The United States has imposed restrictions on activities with Iran under various legal authorities since 1979, following the seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran.

During President Donald Trump’s first term, the U.S. withdrew from its nuclear deal with Iran and ramped up sanctions on its petrochemical industry and other sectors, including construction materials and aerospace equipment.

Various other countries subject to U.S. sanctions include Sudan, Libya and Venezuela.

“We have files in Iran where seafarers are detained, in prison, accused of fuel trafficking. The seafarers and their families come to us desperate, asking for our help,” said Arrachedi. “We have cases of abandonment in Tehran, where even the flag state is Iranian, and they do absolutely nothing to assist these cases.”

Abandonment cases are particularly difficult in countries under U.S. or United Nations sanctions where even buying food or sending money on a humanitarian basis is not possible, according to experts.

Noodles cook on a pot over an open fire in this illustration photo. Stranded at sea, the ship crew survived on meagre rations of one daily meal of instant noodles cooked over a wood fire. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Noodles cook on a pot over an open fire in this illustration photo. Stranded at sea, the ship crew survived on meagre rations of one daily meal of instant noodles cooked over a wood fire. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

“In order for us to send money for humanitarian purposes, it is impossible. Money for visa overstaying is also an issue. We cannot send money to Iran because we cannot breach sanctions,” said Arrachedi.

The United States Department of the Treasury did not respond to a comment request about why there are no sanctions carve-outs for humanitarian purposes.

Go Deeper: The cost of sanctions: Dark shipping fleet fuels human trafficking

Risks and safety

As bombs dropped over Hodeidah last September, Rahul and four Indian colleagues decided they needed to leave Yemen.

The ITF and local partners appealed on their behalf to a local agent to allow them to leave. At the time, foreigners were not permitted to use the nearest airport at Sanaa, and the only option was a 14-hour bus ride to Aden, where they could take a direct flight to Mumbai.

The crew was nervous because the journey would take them through militant-controlled areas peppered with checkpoints set up by groups including Al-Qaeda. Each stop carried the risk of questioning, detention or worse, and they knew a wrong word or a suspicious glance could spell doom.

Arrachedi, who helped coordinate the escape, waited anxiously for updates as the crew passed through checkpoint after checkpoint. His phone would go silent for hours, and each gap in contact felt like a sign something had gone wrong. There was a real possibility that at any point, a suspicious or jumpy militant could have simply shot them, he said.

“They were very exposed and vulnerable,” Arrachedi said. “But what other option did they have?”

Rahul made it home to India, but the ordeal was costly. He is still owed $14,000 in wages for the seven months he spent aboard the MV Captain Tarek, and the harrowing experience convinced him to abandon a seafaring career altogether.

Afraid of retaliation, he has chosen not to seek retribution against the ship owner or the recruitment agent with the authorities in India, worried they could act on their earlier threats.

“Seafarers don’t have the right to become angry,” he said. “For our safety, and for our family’s safety.”

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Ocean Reporting Network.

Reporting: Katie McQue

Editing: Ellen Wulfhorst and Amruta Byatnal

Illustrations: Karif Wat

Production: Amber Milne

Tags

- Poverty

- Workers' rights

- Underground economies