U.S. East coast faces 'competing catastrophes' as fire risk grows

The Jackson Road Fire, which originated at a military bombing range in Dare County, North Carolina, burned through more than 1,000 acres of land in March 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Handout via North Carolina Forest Service.

What’s the context?

Rising global heat is shifting U.S. wildfire risks to unexpected new states.

This story is part of a special series on what the world might look as the planet heats up: What happens at 1.5C?

- With warming, U.S. wildfire threat is spreading to East Coast

- Towns that face floods and sea level rise not prepared for fire

- Managing multiple threats at once proving challenging

NAGS HEAD, North Carolina - Nags Head, a quiet beachfront community of colorful wooden homes in North Carolina's Outer Banks, faces no shortage of climate change-fuelled threats, from wilder storms to sea level rise and flooding.

A survey of some of the coastal resort town's residents, for a state resilience report released in May, found nearly 80% had been impacted by flooding or hurricanes.

But as global temperatures approach a key 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) level of warming that scientists fear could herald a transition to far costlier and deadlier climate change impacts, a new threat is rising in normally water-threatened Nags Head: wildfire.

Western U.S. states, including California, have grown accustomed to dealing with catastrophic-scale wildfires in the face of a relentless increase in "fire weather" - conditions of record temperatures, low humidity and high winds.

But now similar threats are quietly spreading across the nation, including into states not up to now thought of as at significant risk.

North Carolina saw 5,151 wildland fires in 2021, the third most in the country after California and Texas. In March, a thousand acres burned just a short drive from Nags Head, after a fire prevention blaze went wrong.

The eastern seaboard state still ranks 23rd nationally in the area affected by wildfires, with 26,000 acres (10,500 hectares) burned in 2021, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.

But North and South Carolina have some of the largest numbers of properties threatened by wildfire after California and New Mexico, according to a May report by First Street Foundation, a non-profit that maps climate risks.

"Wildfire risk is increasing so much faster than even flood risk is across the U.S.," said Ed Kearns, the group's chief data officer. "And it's likely to affect areas that aren't thought of as wildfire-prone areas right now, but will be soon."

Global temperatures have risen more than 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 Fahrenheit) since preindustrial times, and oil, gas and coal use - the major driver of that increase - are still rising, despite pledges to slash emissions.

Top climate scientists say 1.5C of warming - the more ambitious warming limit set in the 2015 Paris Agreement - could be passed within a decade.

They fear that could trigger irreversible ecological tipping points, from surging sea levels as polar ice melts to spiking temperatures as methane - a potent driver of warming - escapes thawing permafrost.

A hotter planet is also expected to spark more extreme weather, crop failures, species extinctions, migration and soaring personal and financial losses for many people around the planet.

'It's going to burn'

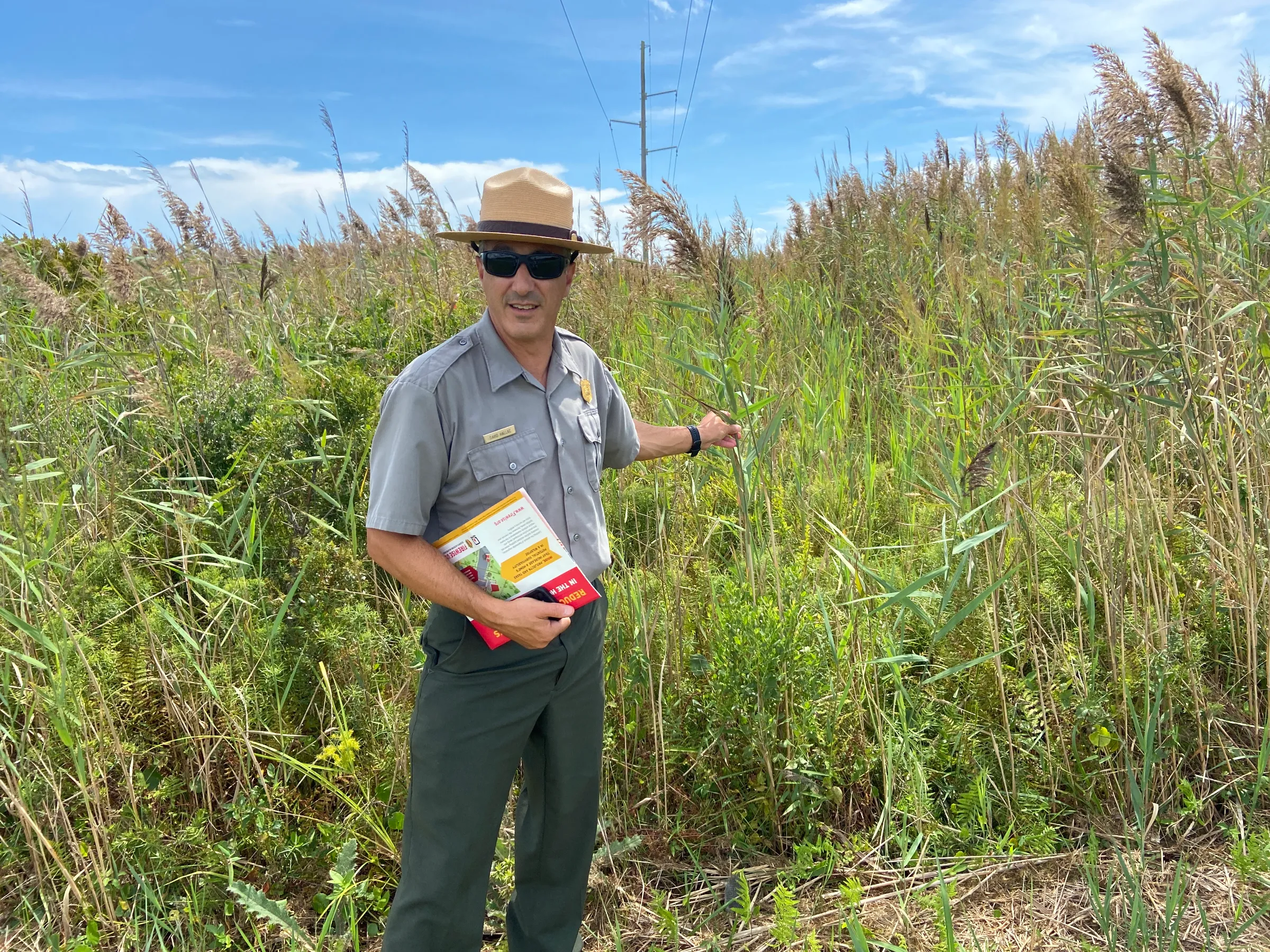

The landscape near south Nags Head is idyllic - blue skies, dried grass and sand dunes that shield the Atlantic Ocean - but David Hallac's concern is palpable as he plucks a stalk of dried reed from the soil and crumbles it in his hand.

"Once the stalk dies like this ... this is extremely flammable," warned the superintendent of the National Parks of Eastern North Carolina.

Miles-long stretches of the reeds, invasive wetlands plants that only grow back thicker after being cut or burned, have proved a management challenge around Nags Head, and threaten to increase the fire risk to nearby homes.

David Hallac, superintendent of the National Parks of Eastern North Carolina, grasps a reed - which can be flammable if not maintained properly – near south Nags Head, North Carolina, September 6, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/David Sherfinski.

David Hallac, superintendent of the National Parks of Eastern North Carolina, grasps a reed - which can be flammable if not maintained properly – near south Nags Head, North Carolina, September 6, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/David Sherfinski.

"You put a match to this, and it's going to burn very, very quickly," Hallac said. Management efforts, from mowing to herbicides, are difficult given the sheer volume of the vegetation, he added.

In a community facing a wide range of climate change-fuelled risks, residents and local leaders are most concerned about worsening storms, floods and sea level rise. That has left officials sometimes struggling to ramp up efforts to cut wildfire risks too.

Riva Duncan, a former fire management officer for North Carolina's national forests, said focusing on all the threats was a challenge in a region with "competing catastrophes".

"It's the hurricanes and the rising water – they're right in (residents') face all the time, and wildfire may not be," said Duncan, now the executive secretary for Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, an advocacy group.

"Which one do you put your time and energy into the most?" she asked. "What's the biggest bang for the buck?"

'Too many fires'

On the Dare County mainland, less than an hour's drive from Nags Head, a huge wildfire torched more than 1,000 acres of land in March.

The "Jackson Road Wildfire" originated from a prescribed burn - commonly used to reduce the risk of fire - which spiraled out of control amid a combination of lower-than-expected humidity, persistent drought, and unforeseen winds.

"A lot of what we do is based on climatology that expects things to sort of be a certain way," said John Cook, a district forester with the North Carolina Forest Service.

"And when you have these weird events that occur, it makes it really hard to plan and work."

Inland parts of Dare County have long endured wildfires. The peat soil there, versions of which are found throughout the southeastern United States, is more susceptible to sustained burning than the wetter and sandier Nags Head area.

But the threat of blazes is growing, including in new places.

Chatting in a command center adorned with awards for fire suppression and prescribed burning, Cook and his colleague John Van Riper reeled off a spate of recent wildfires in Dare County and around the state.

"There's just been so many damn fires," Van Riper said, lowering his voice to a whisper.

"Too many fires," the forest fire equipment operator added.

Cook said steady development in the Nags Head area - including a build-up of trees, shrubs and other flammable vegetation - is increasing the risk of wildfires.

Close to 5,000 properties in the town of Nags Head - 87% of the total - now have some risk of being affected by wildfire in the next three decades, according to First Street Foundation.

That risk in populated areas of Nags Head is, on average, higher than in 70% of communities nationwide, the federal mapping tool Wildfire Risk to Communities shows.

"Hurricanes, fires, floods - we got a little bit of everything here," Cook said.

Recognising the risk

Nags Head Mayor Ben Cahoon said wildfires were a concern but resources were limited in a coastal town where erosion, hurricanes and flooding are more immediate dangers.

He hailed the town's beach nourishment plan which periodically installs fresh sand and plantings to protect beachfront homes and infrastructure – a top priority for a community at risk of being swallowed by rising seas.

The survey of residents released in May, which showed most had been impacted by floods or hurricanes, found only one person so far affected by wildfires.

Still, "we spend so much time talking about floods," Cahoon admitted. "We probably should be a little more attentive to (fire), talk to our citizens a little bit more about it than we do."

Residents, so far, aren't particularly worried.

"I've been here 37 years," said Bryan Whitehurst, a co-owner of Greentail's Seafood Market and Kitchen in Nags Head and a resident of nearby Kill Devil Hills.

"There's been fires, but nothing they haven't been able to put out."

Hot topic?

Elena Shevliakova, a senior climate modeler at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said authorities need to start thinking now about how to protect the public from worsening wildfire threats.

"How are you going to change your management of fires? And how are you going to do urban planning?" she asked.

In Dare County, local, state and federal officials are working to cut the risks with efforts like prescribed burns in Nags Head Woods Preserve and Jockey's Ridge State Park, both of which abut residential neighborhoods.

Residents are slowly coming around to the idea of "good fire" that can cut threats by removing vegetation that burns easily, said Kayla Barnes, a Dare County ranger for the state's Forest Service.

But Hallac, of the National Park Service, said it can be challenging to communicate rising levels of risk to people who might never have seen a big wildfire before.

"I'm sure that if we had a large wildfire that threatened or impacted private dwellings, (it) would become a hot topic," he said. Wildfires "are not a huge issue until they are."

This story is part of a series on what the world will look like at 1.5 degrees Celsius. For the rest of the series, click here.

(Reporting by David Sherfinski. Editing by Laurie Goering and Kieran Guilbert.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Loss and damage

- Forests