Brazil wants farmers to help save the Amazon. Will it work?

An aerial view shows a deforested plot of the Amazon rainforest in Manaus, Amazonas State, Brazil July 8, 2022. REUTERS/Bruno Kelly

What’s the context?

At COP28, Lula detailed his plan to revive degraded pasture land, aiming to fight deforestation and boost farming at the same time

- At COP28, Lula details pasture regeneration plan

- Programme aims to boost farm output, without deforestation

- Challenges include costs, access to technical know-how

RIO DE JANEIRO - Plans by Luis Inácio Lula da Silva to revive vast swaths of degraded pasture are key to his push to protect Brazil's Amazon without alienating farmers, but questions remain - including whether they will agree to stop clearing trees on their land.

During COP28 in Dubai, the leftist president detailed the proposals to ease pressure on Brazil's forests by regenerating up to 40 million hectares (99 million acres) of depleted grazing land - an area roughly the size of Sweden - within a decade.

"We want to convince the people who invest in agriculture ... that it is completely viable to keep the forest standing and (still) have land to plant whatever we want," Lula told reporters at the U.N. climate conference, which ended on Wednesday with a deal to transition away from fossil fuels.

The launch of the plan coincides with efforts by the agricultural powerhouse to improve its environment record as the country braces for new EU regulations banning deforestation-linked commodities.

Brazil is one of the world's biggest beef exporters, with more cattle than people, and in the Amazon, 86% of the areas deforested between 1985 and 2020 became pastures, according to an analysis from environmental nonprofit Imazon.

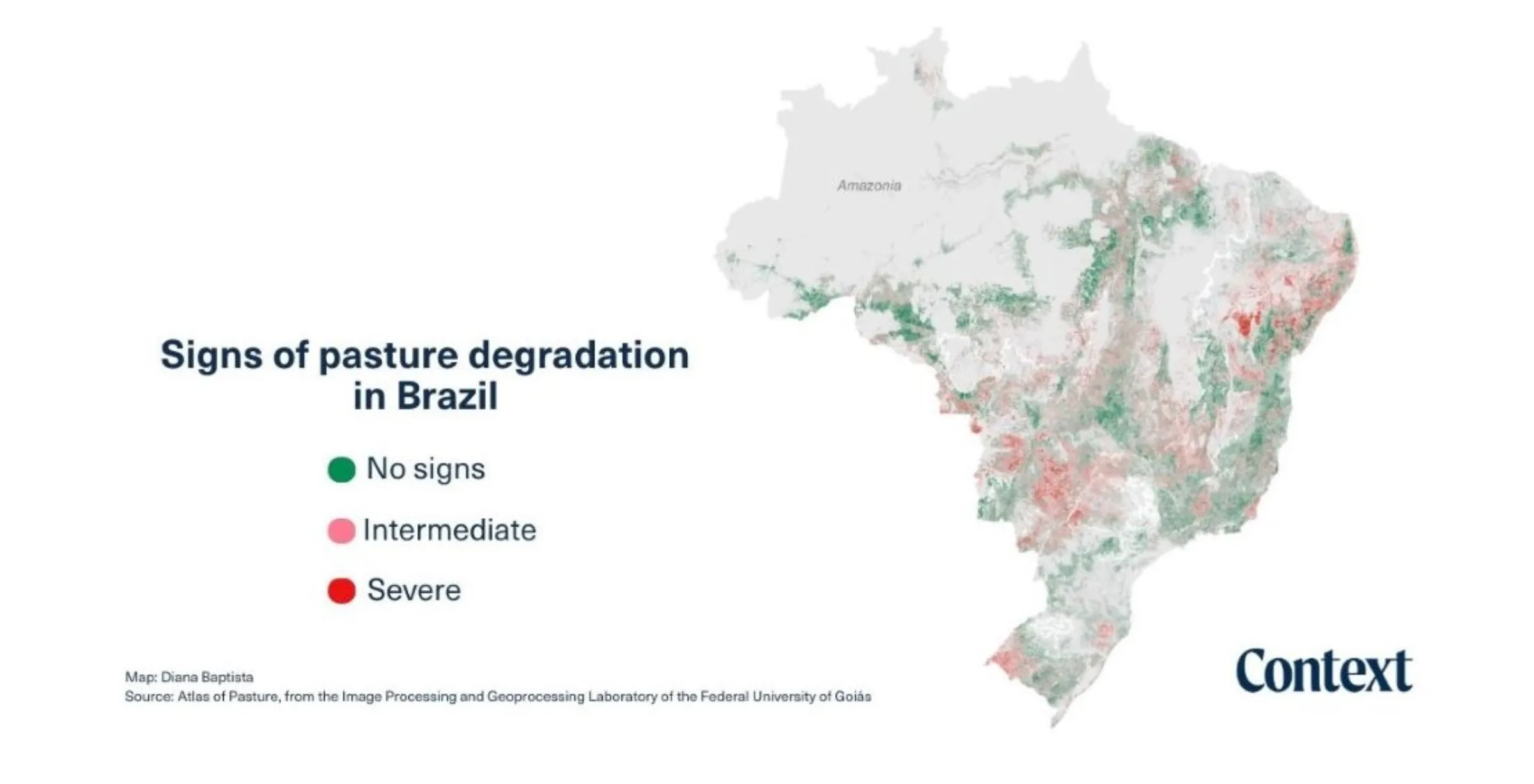

Nationwide, pastures cover about 160 million hectares (395 million acres), but 63% of them are degraded, according to data cited by the government, severely limiting the land's productivity, whether for ranching or grain farming.

That creates an incentive for farmers to clear new areas through deforestation in endangered biomes including the Amazon and the Cerrado tropical savanna.

The new plan seeks to make buying or leasing degraded land a more attractive proposition instead, and coincides with Lula's efforts to improve ties with the powerful agribusiness sector.

Farm industry backers control 374 of Brazil's 511 congressional seats, and Congress has been voting over the last couple of decades to make more room for private farmland over forest land.

Lula took office this year with promises to reverse the surge in deforestation that took place during the government of his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, who was supported by the farm lobby, and data indicates he has had some success.

Deforestation in the Amazon dropped 22.3% in the 12 months ending July 2023 year-on-year, reaching the lowest level since 2018 - when Bolsonaro was elected, according to official data. Still, in the Cerrado, deforestation rose 3% over the same period.

Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva delivers a national statement at the World Climate Action Summit during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, December 1, 2023. REUTERS/Thaier Al Sudani

Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva delivers a national statement at the World Climate Action Summit during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, December 1, 2023. REUTERS/Thaier Al Sudani

Forest code

Launched in a decree last week, the pasture plan could be central to more sustained progress to fight deforestation because it aims to keep the country's farmers happy by giving them an incentive to boost output on existing farmland.

Under the regeneration push, farmers would be encouraged to invest subsidised loans in either improving pasture productivity or converting pasture into cropland, making use of sustainable techniques such as soil recovery, no-till farming, use of more nature-friendly fertilisers and pesticides.

Brazil's Parliamentary Agricultural Front (FPA) welcomed the programme's launch, saying that if implemented effectively it could be a "significant tool in the promotion of sustainability" in farming.

Nelson Ananias Filho, sustainability coordinator with the Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock, said farmers were ready "to give their contribution to this ambitious target".

Crucially, however, the programme also stipulates that farmers should not increase their carbon emissions by changing land use within 10 years of joining the programme.

That could be a sticking point because farmers are legally allowed to clear trees on private land under the terms of the 2012 Forest Code, which was pushed through by agribusiness backers in Congress.

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista

The regulations require natural vegetation to be retained on only a portion of privately owned rural land, and expanded the area that can be legally cleared.

"We need to promote initiatives to fight illegal deforestation, but at the same time guarantee deforestation (that occurs) under the law, as predicted by the Forest Code," Filho told Context.

Another possible hurdle for the pasture recovery plan is the hefty price tag - much of which the government hopes major importers of Brazilian food will finance.

Agriculture Ministry studies estimate it could cost an average of $1,500 to $3,000 per hectare, meaning the price tag for 40 million hectares could be as much as $120 billion.

Brazil already offers credit lines for farmers to convert degraded pastures into more productive crop fields, but that currently accounts for just 2% of Brazil's subsidised farm credits – about $1.2 billion.

In addition to funding already available in Brazil, the government says Japan, South Korea, China and Saudi Arabia have shown interest in backing investments in regenerative farming.

"We want the world to put green, soft loans (into the programme)," said Carlos Augustin, special advisor to Brazilian Agriculture Minister Carlos Favaro.

"Countries want sustainability, to contribute with the fight against climate change, and we are offering all this: more food, without deforestation," he said, adding that the exact terms of potential investment in the programme were still being negotiated.

The programme's decree says resources could also come from existing sources, which environmental advocates said could be an opportunity to redirect subsidized government loans to cattle ranchers and soy farmers in Amazon states.

"Independently from raising more money, you must make better use from the money that already exists", said Paulo Barreto, a researcher at Imazon.

Other challenges include ensuring technical experts are on-hand in remote areas, said Patrícia Menezes, a researcher at the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), which will provide technical support.

"It's a very big country, with very unequal degrees of development. There are regions where those with expertise do not want to live," she said.

Reforestation

Brazil also launched an Amazon restoration project at COP28, which will help finance reforestation in the "arc of deforestation" that spans the Amazon forest's southern and eastern fringes, with state development bank BNDES announcing initial funding of 1 billion reais ($200 million).

Brazil's forest and farmland restoration initiatives go hand-in-hand, said Fabíola Zerbini, director of Brazil's Department of Forests within the environment ministry.

Restoring natural areas is vital for replenishing water basins - a key step in pasture regeneration, she said.

Ultimately, Barreto said, the success of the pasture regeneration plan hinges on making the proposition a better business opportunity for farmers than deforestation.

To help tip the balance, he said the government should improve tracing systems that allow buyers to avoid products from areas that have been newly deforested - whether legally or illegally, he said.

"If it's too easy to deforest, people will prefer to do that than invest in (land regeneration) technology," he said.

($1 = 4.9561 reais)

(Reporting by Andre Cabette Fabio; Editing by Helen Popper.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Adaptation

- Agriculture and farming

- Loss and damage

- Biodiversity