Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Cattle stand in pens where they arrived from different ranches in the Amazon basin before being trucked to a port for export overseas, in Moju, Para state, near the mouth of the Amazon river, November 7, 2013. REUTERS/Paulo Santos

Illegally converting forests to ranches and farms is an established process in Brazil. Here's how to change it

RIO DE JANEIRO - Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has promised to halt deforestation in the Amazon as tree clearing threatens global climate stability and causes biodiversity loss in the rainforest.

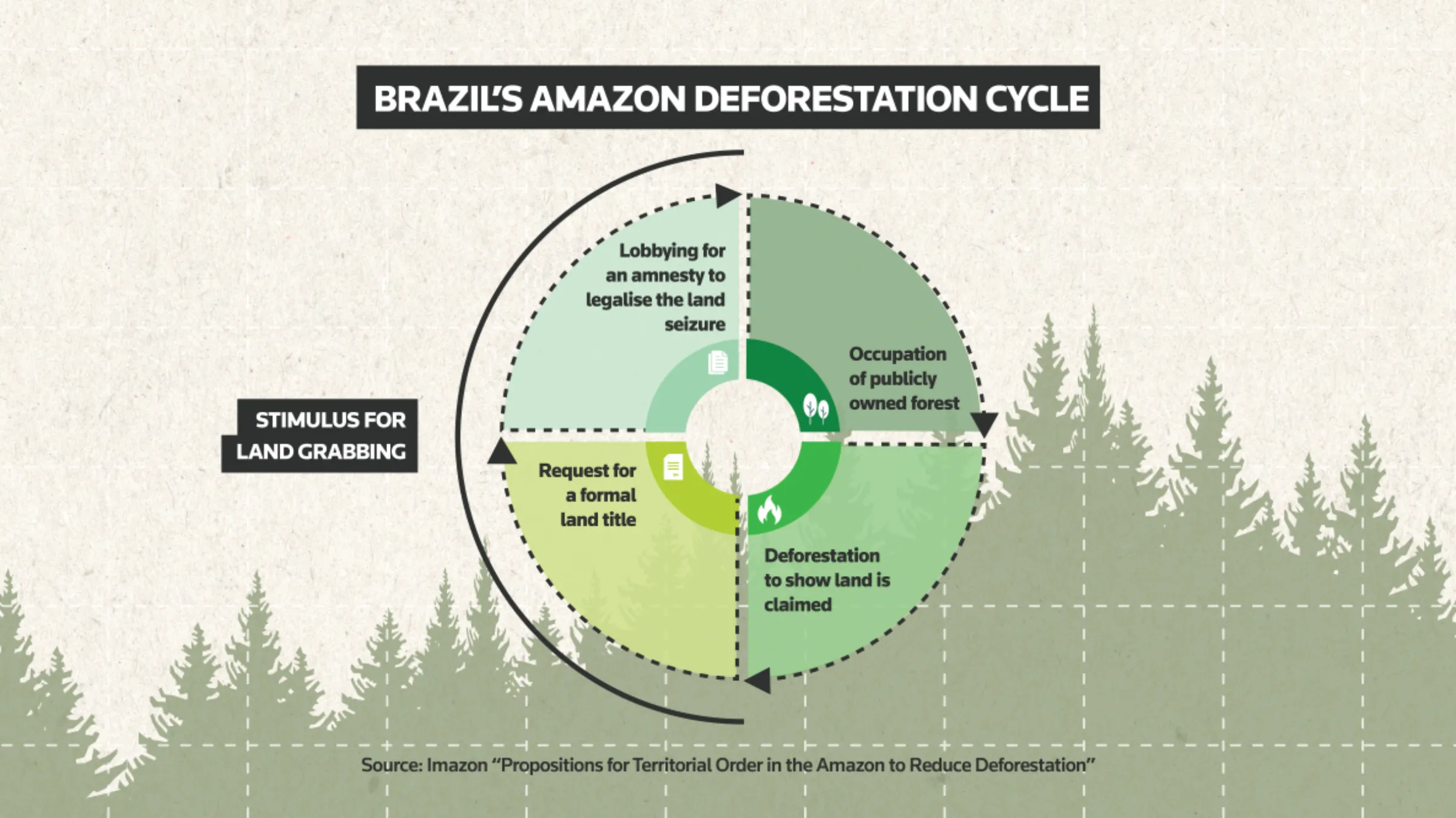

But to succeed, experts say he will have to break a cycle of land grabbing that has led huge swaths of Brazil's Amazon to be cleared by cattle ranchers, speculators and others - often working in partnership with illegal loggers.

Here's how the cycle works - and how it might be broken:

About half of the deforestation threatening Brazil's Amazon region happens on publicly owned land as land grabbers try to stake a claim to areas that could be used for cattle ranching, grain farming, real estate speculation or other commercial and financial uses.

After illegally deforesting the land, would-be "owners" then register a claim to it with local, state or national authorities. Periodic amnesties then formalize those claims, in turn driving a new round of speculative land grabbing.

In Brazil's Amazon, publicly owned "undesignated" land officially covers about 58 million hectares (143 million acres), an area bigger than Spain. Without specific protections, the land can subsequently be transferred to private ownership.

There is a lack of clarity in public records over the status of roughly another 85 million hectares.

Both federal and state laws allow land tenure regularization programs as a way to grant property rights to longstanding settlers. But critics say such provisions are exploited by land grabbers to secure ownership of areas they occupy.

Under one of the most recent federal regularization laws, settlers could request official ownership of federal land occupied before 2004.

That date was later extended to 2011, and there is political pressure to extend it further.

Similar processes have gone on at the state level, passing state-owned land to private ownership. Some states have cut-off dates for settlement as late as 2017, or no date at all.

Researchers say the process has encouraged land-grabbers to illegally deforest and occupy public Amazon areas, betting that windows to legally claim them will be opened in the future.

Flowchart of Brazil's Amazon deforestation cycle

Flowchart of Brazil's Amazon deforestation cycle

In order to request ownership of public land, claimants must show proof that the area is occupied and being put to some economic use.

One of the most common ways to do that is to clear land and rear cattle on it. Cattle can be herded into remote sites and fed on pasture alone, making ranching the most viable first productive use of deforested land in isolated regions without good roads or other means of transportation.

Analysis from environmental NGO Imazon, based on data from the nonprofit MapBiomas, indicates that 86% of the areas deforested in Brazil's Amazon between 1985 and 2020 became pasture.

In recent decades, Amazon states have driven much of the expansion in Brazil's cattle numbers. With 220 million animals - more than Brazil's human population of 214 million - the country is one of the world's biggest beef exporters.

None of Brazil's Amazon states currently prohibits granting private land titles over illegally deforested areas, according to a 2021 report from Imazon.

Once in hand, private titles enable farmers to request loans, which are often used to fund more deforestation.

Public land, besides being handed out in private land titles, can be designated as a conservation area under Brazilian law.

Conservation areas have different types of protection, from national monuments that are fully protected, to sustainable development reserves, where some level of economic exploitation is allowed.

Public land can also be recognized as Indigenous or "quilombola" territory, the latter controlled by communities of descendents of slaves brought to Brazil.

Research indicates that the creation of such protected territories is especially effective in curbing deforestation.

(Reporting by Andre Cabette Fabio; Editing by Laurie Goering and Helen Popper)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles