Can AI 'digital twins' help protect us from climate disasters?

Computers at the Jülich Supercomputing Centre in Jülich, Germany, June 10, 2022. Forschungszentrum Jülich/Sascha Kreklau/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

What’s the context?

As climate risks rise, the race is on to use better predictions from supercomputers and AI tools to keep people and assets safe.

- Computer simulations offer a new tool to plan climate adaptation

- Some say data quality in models is more important than visuals

- Experts worry AI will leave hard-hit poorer communities behind

LONDON - When Storm Ruby hit Sunford City in England's low-lying East Anglia region, elderly resident Arthur was trapped at home alone as floodwater seeped into his basement and his power cut out. He could not reach his grandson Jack for help because the phone network was down too.

Fortunately, the storm, the city and the people involved are all fictional, made up for a pilot programme that uses virtual duplicates of physical assets, allowing scientists to simulate climate change impacts using artificial intelligence (AI).

"What's become clearer over the last few years is how we can use 'digital twins'... to better understand these climate risks and help us make decisions," said Sarah Hayes, engagement lead for the UK government-supported Climate Resilience Demonstrator (CReDo).

The project harnessed real data from power, water and telecoms companies operating in an East Anglia town, combining information on their assets with climate projections to simulate pressures on infrastructure across different scenarios.

An interactive app on the disaster in Sunford City, along with a short film featuring Arthur and Jack, went live during the COP26 climate conference last November to show how climate shocks like floods can unleash a wave of problems across key services.

"The problem with the cascade effect is you're getting people in dry areas who are affected by strategic assets which are in flooded areas," Hayes said.

As floods, droughts and wildfires present an increasingly grave threat to human lives and livelihoods, efforts are underway to explore how 'digital twins' could reduce the harm.

Proponents say the visualisations - which encompass large Google-Earth-type 3D maps, as well as specific processes to optimise things like energy efficiency - can provide vital information to guide governments and companies in their work to boost climate resilience.

"If you tailor the information that comes out of the twins to the needs of a decision-maker and they see that this is actionable for them, it leads to action," said Wilco Hazeleger, dean of the geosciences faculty at Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

Hazeleger is an advisor on the European Commission's Destination Earth initiative which aims to build global 'digital twins' in collaboration with Europe's space, satellite and weather forecast agencies.

Analysts say advancements in AI and computing in projects like Destination Earth have the potential to improve the speed and accuracy of climate and weather models, including producing more detailed information to pinpoint local impacts.

"Downscaling basically tries to define a relation of this coarse-scale climate information to what really happens in the city, or in the valley, or on the mountains," said Martin Schultz, a senior researcher at Germany's Jülich Supercomputing Centre.

New 'exascale' supercomputers are being built, including at Jülich, which can perform a 'quintillion' calculations per second - about 100,000 times faster than Apple's iPhone 12, he said.

That will allow people to better predict things that affect the weather, like how clouds behave, while the higher data resolution could help decision-makers in cities, Schultz said.

'Fancy new name'

Others are more sceptical of the need for 'digital twins'.

"The name can be the lipstick on a pig," said Dan Travers, co-founder of Open Climate Fix, a non-profit that applies machine learning to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as by improving weather forecasts to make solar energy more predictable.

AI tools can augment climate models, especially for understanding weather, Travers noted - but he believes the quality and reliability of data, and how it is used, are more important than 'digital twin' visualisations that can be hard to build.

'Digital twin' is a "fancy new name" for scientific models that have been around for years, said Josh Hacker, co-founder of Jupiter Intelligence, a Silicon Valley firm that analyses climate risks.

Those models have long fed into research, such as reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The quest now is to turn the data generated by the models into information that can be used for practical decisions, something governments have been slow to do, he added.

"That gap is where the private sector has always innovated," said Hacker.

Given the threat of damage to trillions of dollars' worth of global assets, the market for information that can protect them is expected to become significant - especially as companies are increasingly being required to report on climate risks to their business.

More than 90% of the world's largest companies will have at least one asset highly exposed to the physical impacts of climate change by the 2050s, according to ratings provider S&P Global.

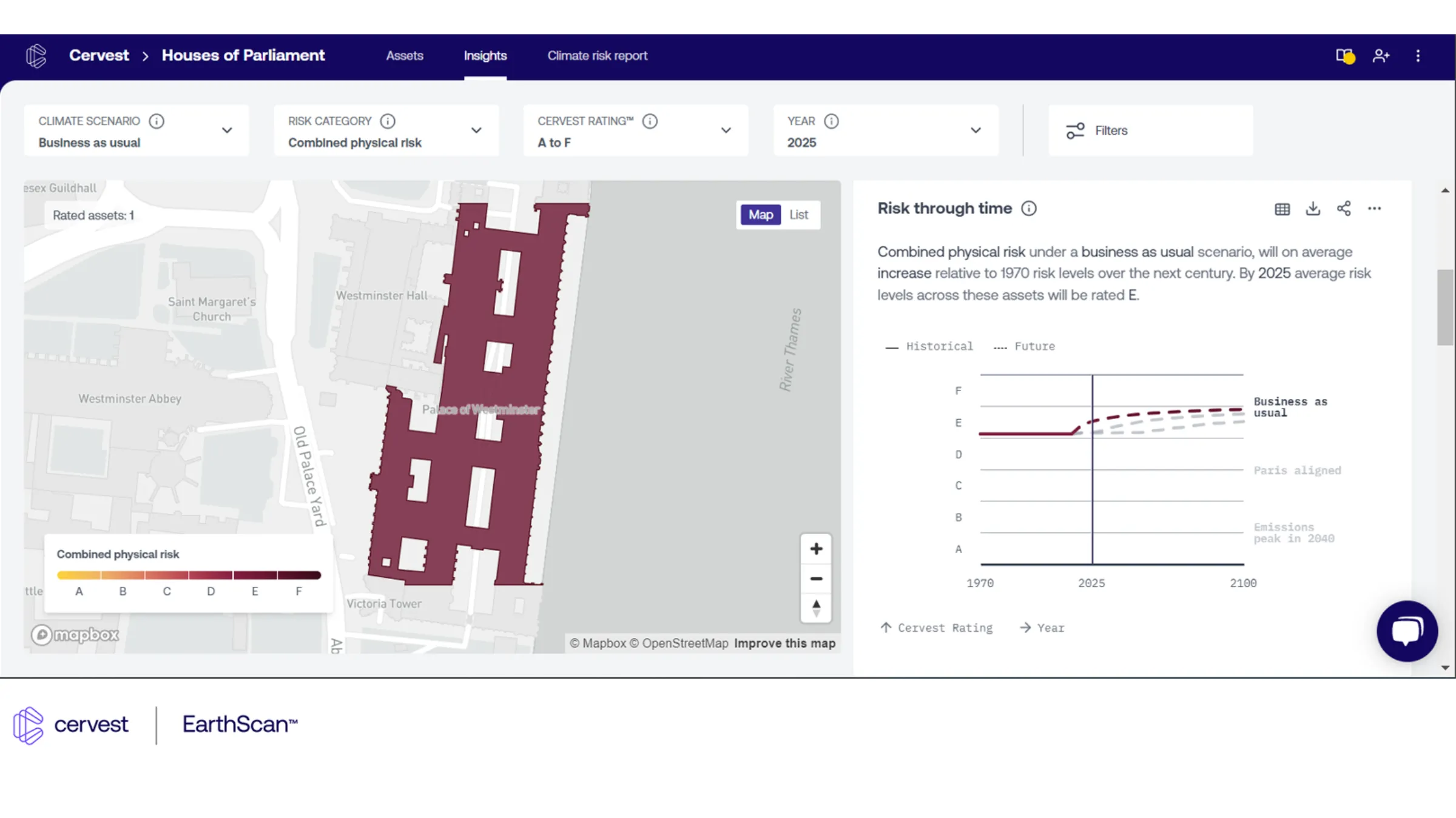

London-based Cervest is another company that aims to help deal with that threat.

It combines a range of data, including publicly available scientific models, then uses machine learning to analyse climate-related physical risks facing assets like factories, hospitals and dams, from heat stress and flooding to high winds.

It then rates the risks to each asset, and has so far catalogued 500 million assets globally.

"Mass personalisation, I think, will drive people's incentives," said Iggy Bassi, chief executive of Cervest, which - like Jupiter - shies away from the 'digital twin' label.

Cervest's visualisation of combined climate risks for Britain's Houses of Parliament in 2025. Cervest/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Cervest's visualisation of combined climate risks for Britain's Houses of Parliament in 2025. Cervest/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Leading technology companies are also applying AI to tackle climate risks.

Google, for example, says its machine learning-enabled flood forecasting initiative is helping issue flood alerts covering an area with more than 360 million people in India and Bangladesh.

The company takes thousands of satellite images to build a digital model of local terrain, using AI to simulate how rivers could behave, and then combines the results with government measurements to generate accurate local flood alerts.

A survey in collaboration with Yale University in India's Bihar state in 2019 found nearly two-thirds of households that received Google's flood alerts took some steps to avoid damage before the water hit, such as safeguarding livestock.

Digital divide

Nonetheless, questions remain about how data and AI should be employed safely and effectively to predict climate risks.

Utrecht University's Hazeleger said data should be as open as possible to maximise its impact on society and maintain trust in science. But, he added, Russia's invasion of Ukraine has made knowledge security and safety an even bigger issue than before.

"People can use (the data) that have other targets and means that are not ethically sound according to our values and norms in an open society," he said.

Another problem with increasingly powerful climate predictions is the global inequality in computing.

"Inherently, AI is a technology that can be leveraged by industrialised nations... much more quickly and effectively," said Lynn Kaack, an academic at the Hertie School in Germany and co-founder of non-profit Climate Change AI.

Kaack said AI is increasing the global digital divide, leading to the danger that large European or North American companies run projects in poorer countries with little input from local communities and their knowledge.

"We need to work against that to make sure that these (AI) tools are also beneficial for increasing equity," she added.

(Reporting by Jack Graham. Editing by Megan Rowling.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Tech and climate

- Adaptation