How one river highlights South Africa’s land inequality

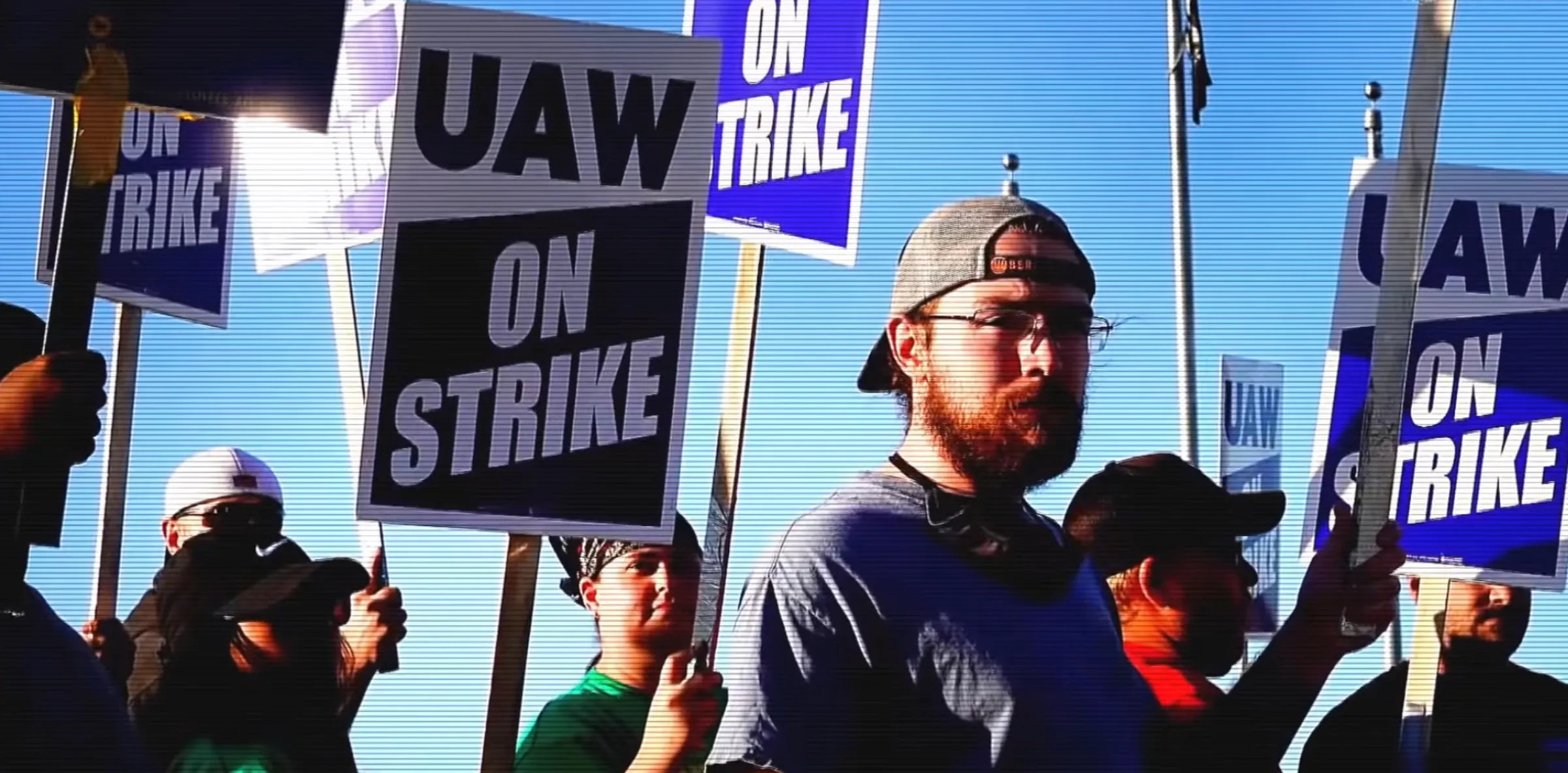

The Liesbeek as seen from one of the Friends of the Liesbeek rehabilitation sites not far from the Amazon development in Cape Town, South Africa, September 6, 2023. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

What’s the context?

From Indigenous rights to environmental protection, Cape Town's Liesbeek river has become a symbol of land justice in South Africa

- Land inequality a hot topic in South Africa

- Different social causes clash over access to river

- Jobs, housing, indigenous rights, environment spotlighted

CAPE TOWN – The Liesbeek River snakes down from Cape Town's iconic Table Mountain for just 9 km (5 miles), but nevertheless has become the focus of a battle between retail giant Amazon, Indigenous groups, green activists and land claimants.

Land is an extremely emotive issue in South Africa. Nearly 400 years of Dutch and British colonial rule and four decades of apartheid saw waves of land grabs and mass evictions of Black, Indian and mixed-race people to create white-only areas.

Across the country, civil society organisations are now engaged in a host of land disputes, but the Liesbeek has seen more than its share as a number of groups compete for their voices to be heard in a raft of legal cases to decide the fate of the river.

The river has become emblematic of the myriad of sometimes conflicting land disputes in a country struggling to right the often-overlapping wrongs of the past.

"The river is the thread that connects all these very big, unaddressed issues in the country, like land restitution, environmental protection and indigenous rights, " South African land researcher Nick Budlender told Context.

Nearly 30 years after apartheid, South Africa is battling high unemployment and inequality, spurred on by corruption and maladministration. Major investments such as Amazon's, which could create thousands of jobs, are badly needed.

Amazon referred questions to its local development partners, the Liesbeek Leisure Properties Trust.

The trust said the "River Club development" was not just about Amazon, but would also "house a number of corporate, retail and residential tenants", including affordable housing units, an ecological corridor with more than 1 million plants and a heritage centre managed and run by Indigenous groups.

While some groups of the Indigenous Khoi people have signed into the project, others fiercely oppose it.

"This river is our connection to our history and the environment," said Tauriq Jenkins, of the Goringhaicona Khoi Khoin Indigenous Traditional Council (GKKITC), one of the most vocal opponents.

"Now history is repeating itself," he said, standing on a small hill looking onto the site, previously a golf course, where construction workers had begun work on the project.

Heritage, justice, environment

The 15-hectare (12-acre) River Club development site is where the Khoi and San peoples fought off a Portuguese attack in 1510.

After the Dutch defeated the Khoi in 1659, they brought in slaves from countries including Malaysia, Madagascar and India to farm the land.

Upstream from the Amazon site, the descendants of some of those enslaved people have been locked in their own legal battles after they were forcibly removed from the 28-hectare (69-acre) Protea Village land at the foot of Table Mountain in the 1960s.

"Our heritage is rooted in this entire area," said Barry Ellman, descendant of the original Protea Village community and chairperson of the Protea Village Communal Property Association.

The evicted families won the right to 12-hectares (5-acres) in 2006, but have not been able to begin development due to legal challenges, initially from disgruntled residents of a wealthy neighbouring suburb until 2011, then from a local environmental group, Friends of the Liesbeek (FOL), which argued development would harm the river.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court of Appeal dismissed an appeal application in May made by local civil society groups trying to stop construction downstream at the 4.6 billion rand ($243 million) River Club site set to house Amazon Africa.

Jenkins said a rival Khoi group had backed the project due to what he called an orchestrated attempt by Amazon's local partners to divide Indigenous groups that included a legal challenge to his leadership of GKKITC.

The trust developing the site responded that "any suggestion of impropriety is categorically denied", and said Jenkins did not represent the views of all of the GKKITC.

The city of Cape Town welcomed the court decision allowing the building to go ahead and said it would bring enormous "heritage, environmental, economic, infrastructural and other benefits to Cape Town and its residents."

The city said the development would bring more than "5,000 construction jobs and approximately 19,000 employment opportunities".

But Jenkins said he believed those numbers were inflated and said he and other GKKITC members would appeal.

"Our heritage is not for sale," he said.

Apartheid legacy

Protea Village, however, has proved an example of how communities and competing interests can eventually come together.

Friends of the Liesbeek work along the full stretch of the river to remove alien vegetation, plant indigenous trees and grasses, and monitor the return of local wildlife. Most of their time is spent immediately upstream from the Amazon site.

"This feels like healing to me," said FOL chair Nicholas Fordyce, pointing out the reintroduction of rare plant species and the return of bird species like malachite kingfishers and African black ducks.

Fordyce said the rehabilitation work included excavating a channel to reconnect the river with a floodplain for flood mitigation - work he says likely stopped the Amazon site flooding during recent rains.

Though unhappy with the Amazon development, Fordyce said FOL chose not to take on a "David versus Goliath" battle, but challenged parts of the Protea Village development in 2021 to protect a critical wetland in the upper reaches of the river.

After ongoing conversations and legal proceedings with FOL, the Protea Village families revised their development plans to further expand the green belt that aims to reduce density in the area that concerned FOL.

FOL then dropped its planning appeal last month and residential development is expected to begin in October next year.

"The legacy of apartheid means the environment has to pay the price for our political history," said Fordyce.

The Amazon site though has failed to bring together disparate communities, according to Jenkins.

"We have to continue to fight, this development has divided communities, not brought us together," he said.

The river is a case study spotlighting the interconnectedness of South Africa's social issues and can be a lesson for future land claim victors, Ellman said.

"We cannot see this project in isolation. Land restitution is a constitutional imperative and it doesn't have to bulldoze environmental issues," he said, pointing out the church and graves of his ancestors on the site.

"If land inequality is not addressed, we won't see stability in this country," he said.

($1 = 18.9228 rand)

(Reporting by Kim Harrisberg; Editing by Jon Hemming)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Race and inequality

- Economic inclusion

- Indigenous communities