Direct cash scheme in U.S. South aims to lift Black women out of poverty

A woman looks for information on the application for unemployment support at the New Orleans Office of Workforce Development, as the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues, in New Orleans, Louisiana U.S., April 13, 2020. REUTERS/Carlos Barria

What’s the context?

As interest in guaranteed income programs grows, a major scheme in the U.S. state of Georgia aims to support Black women facing gendered and racial barriers to wealth.

-

Hundreds of Black women will get regular cash payments

-

Scheme aims to tackle gender, race wealth barriers

-

Rising number of cities experiment with guaranteed income

WASHINGTON - Applying for jobs, picking up gig work as a delivery driver, looking after her six children: life is an endless juggling act for single mom Sheila as she struggles to make ends meet and provide for her family in Atlanta, Georgia.

"It's tiring, because I'm (trying) to find steady income," said Sheila, 33, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy.

But this week, she will start receiving regular cash payments totaling $20,400 over two years under a guaranteed income program supporting hundreds of lower-income Black women in the state.

"It's going to be a big help," she said.

Sheila is one of about 650 Black women set to get cash transfers with no conditions on how the money is spent under a program organized by GiveDirectly and the Georgia Resilience and Opportunity (GRO) Fund, two nonprofit groups.

Interest in universal basic income and other guaranteed income programs is growing across the United States and beyond, with dozens of schemes and pilots taking place nationwide.

Organizers say it is the largest ever guaranteed income initiative in the U.S. South, aiming to help Black women who suffer entrenched economic inequality as a result of systemic gender and racial barriers to wealth.

In the United States, Black women make roughly 61 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men - translating to a loss of more than $23,000 a year, according to a 2019 analysis by the National Women's Law Center.

Black women in Georgia are roughly twice as likely as white women to be living in poverty, according to the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, a nonprofit, and nationally they are less likely to have bounced back from COVID-19 job losses.

"We just have it hard," said Taneisha, a 32-year-old who was also accepted into the Georgia program, as she described the challenges facing Black women.

"We're always looked at to be superwoman but we can't get the superwoman level of pay, respect, and other things."

Clear benefits

Champions of direct cash support schemes say they are highly effective in tackling poverty, improving health and well-being, and promoting economic empowerment.

Opponents say they can disincentivize people from seeking employment - though numerous studies conclude otherwise.

"Philosophically, it's easier to get the program (enacted) if work is a requirement," said Doug Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a center-right think-tank.

Holtz-Eakin also raised concerns that publicly-run programs could distort local economies with higher taxes to pay for them, and in turn incentivize higher earners to move out of the area.

An increasing number of countries and U.S. cities have in recent years experimented with universal basic income schemes, or other guaranteed income initiatives which typically target a specific demographic group.

"The data speaks for itself – people worked more. People were less sick, less anxious – people spent more time with their families," said Michael Tubbs, the former mayor of Stockton, California, which launched its own guaranteed income scheme.

There have also been recent programs in the U.S. targeting women of color and Black mothers - though not at the scale of the new initiative out of Georgia, which is privately funded.

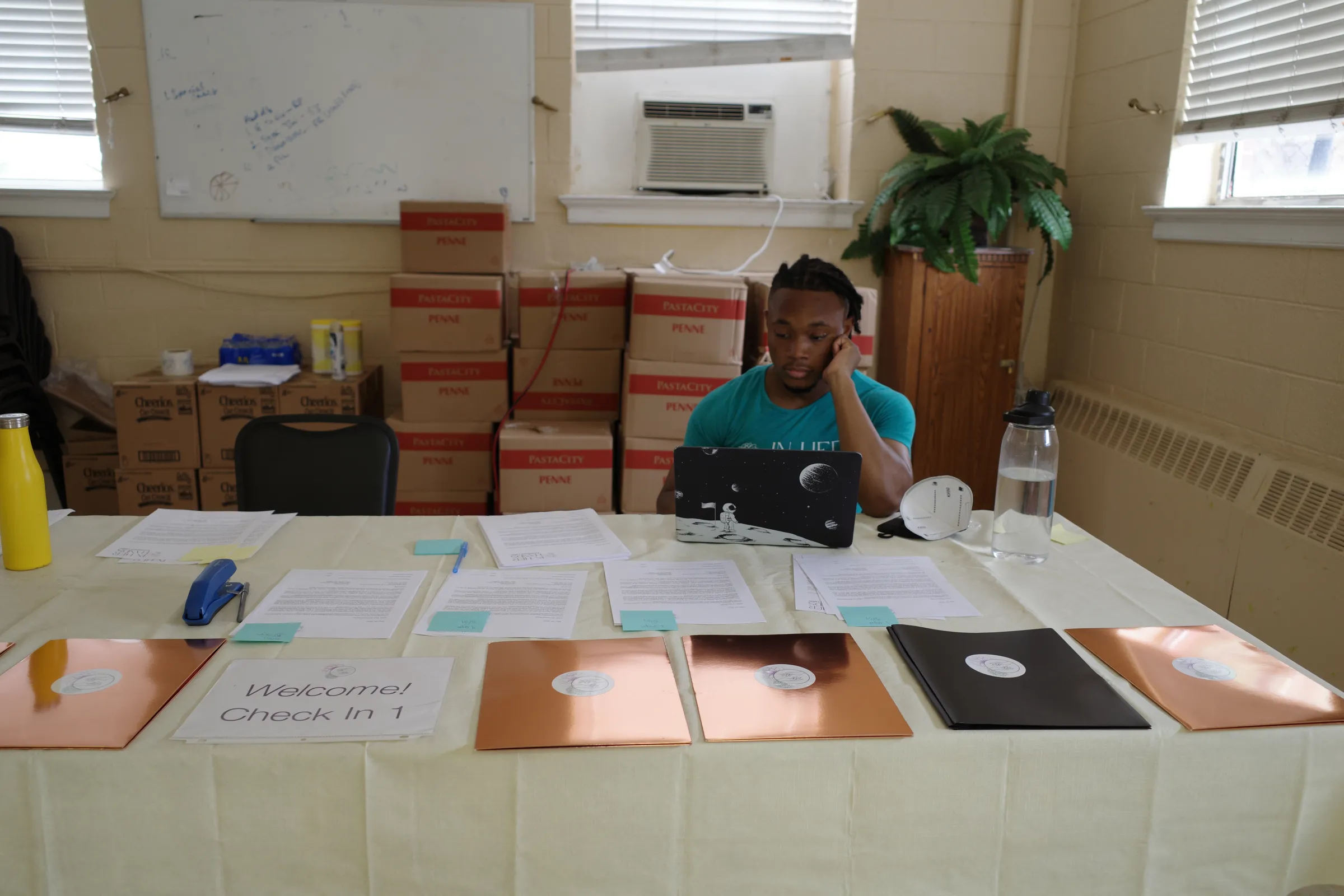

Christian Keith with the Georgia Resilience and Opportunity (GRO) Fund is pictured at Ebenezer Baptist Church, an enrollment site for the In Her Hands guaranteed income program, in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, on May 31, 2022. InHerHands.us/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Christian Keith with the Georgia Resilience and Opportunity (GRO) Fund is pictured at Ebenezer Baptist Church, an enrollment site for the In Her Hands guaranteed income program, in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, on May 31, 2022. InHerHands.us/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Civil rights legacy

Enrollment for residents in Atlanta's Old Fourth Ward neighborhood has been taking place at Ebenezer Baptist Church, whose previous pastors included civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King Jr., who was also an advocate for guaranteed income.

Participants must earn an annual income of no more than two times the federal poverty level, which varies by household size but for a family of four works out at $55,500.

Half will get 24 monthly installments of $850, and the other half will get a lump sum of $4,300, followed by 23 months of $700 payments, as organizers experiment to find the most effective way to deliver the money.

Taneisha plans to pay off debt and potentially find a better apartment for herself and her two children.

Sheila also hopes to move into a bigger apartment, and aims to get a hair product business off the ground, which could offer her steadier work and income.

"I have four daughters, so of course I have to be an example for them," she said.

GiveDirectly is working with Appalachian State University to research the impact of the scheme, with the aim of providing data to steer future anti-poverty initiatives.

One goal is to assess the impact of guaranteed income on "racialized economic inequality," said Miriam Laker-Oketta, research director at GiveDirectly, who said they would be following up with women to learn about their experiences.

"We want to hear the effects on their health, on their income, on their assets, family relationships, well-being, and resilience," she said.

Meanwhile, organizers say they can already see the impact on the women taking part.

"They leave happy – either crying or smiling or jumping," said Shonda Godfrey, an enrollment officer, as she described the reaction of participants.

"You can have the relaxation of 'I can feed my kids this month'."

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Gender equity

- Unemployment

- Pay gaps

- Wealth inequality

- Housing

- Race and inequality

- Innovative business models