Fear of deportation grips undocumented women on California's farms

Crews package table grapes for shipment to supermarkets right in the vineyard in Kern County, California, August 26, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons

What’s the context?

Women who are undocumented farm workers in California fear for their families amid the government's immigration crackdown.

- Nearly half of U.S. agricultural workforce is undocumented

- About half of undocumented women in U.S. have young children

- Undocumented women in U.S. are paid less than male coworkers

LOS ANGELES - At this time of the year, Maria should be hard at work picking grapes in California's Central Valley, a crop so huge that it typically takes tens of thousands of workers to harvest.

This year, however, she is staying away from the vast vineyards, terrified of being arrested and deported in federal immigration raids targeting undocumented farm workers across the country.

While most of those being apprehended are men, the consequences can be devastating for families when the women who care for them are arrested. Women carry the bulk of responsibilities for children and elderly relatives, and deportation can mean leaving behind young or vulnerable family members who need their support.

"I'm very scared," said Maria, 45, whose name has been changed because she is undocumented and who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Her two children, ages 10 and 20, have hearing disabilities that hamper their ability to communicate.

“My daughter is asking ‘What will happen if you get deported?’ She’s the one who's the most afraid," she said.

Maria, whose children are U.S. citizens, has not worked since June when the administration of President Donald Trump scaled up its increasingly aggressive deportation plans.

More than 40% of the nation's agricultural workforce is undocumented, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

Under pressure from the agriculture industry, on June 12, Trump instructed Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other federal agencies to stop focusing on farm workers.

Those opposing the crackdown included the American Farm Bureau Federation, an advocacy organisation representing two million farmers and ranchers.

But the respite was brief. The government reversed its stance four days later, putting hundreds of thousands of immigrant workers back in ICE crosshairs.

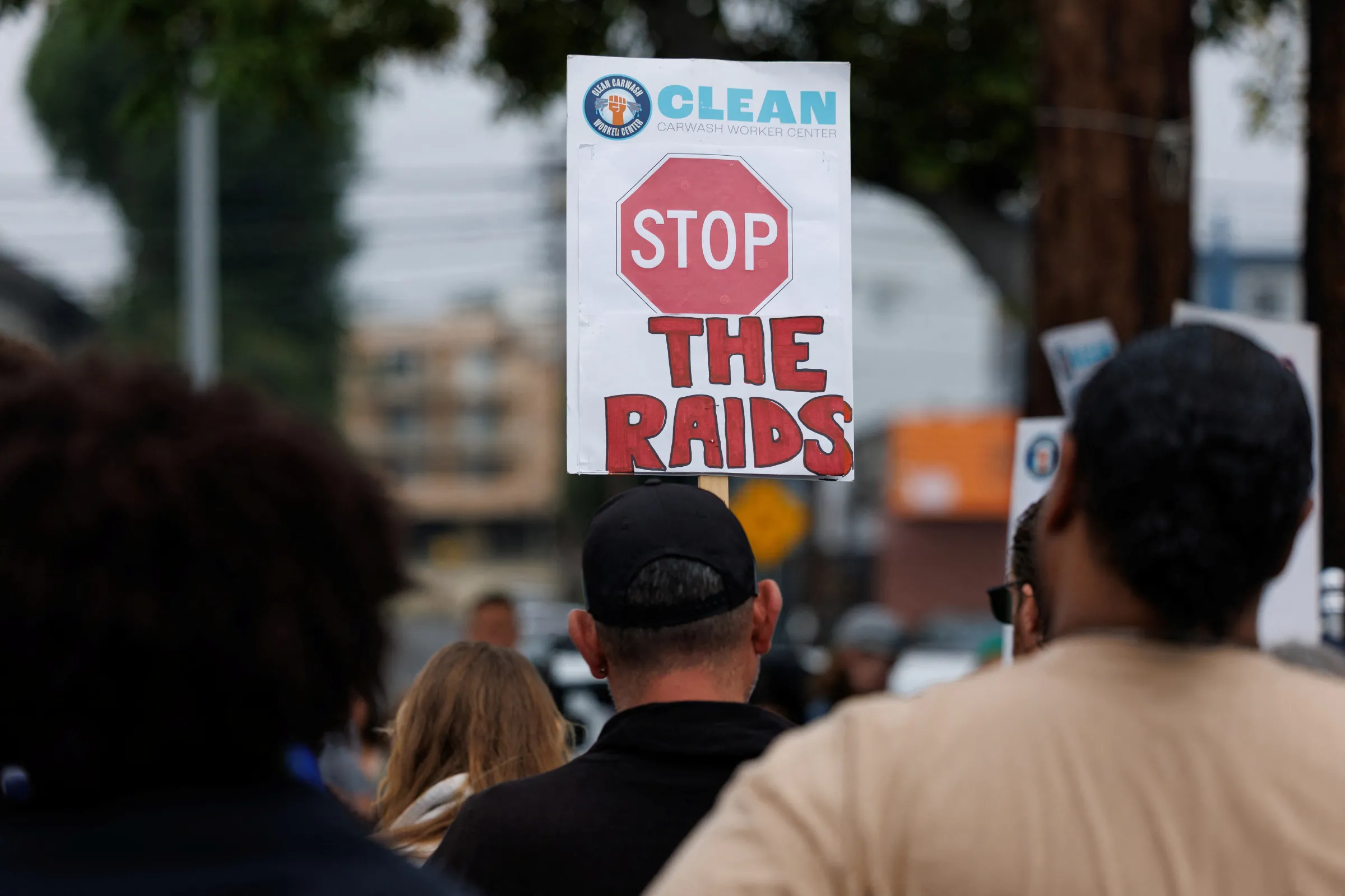

Since then, raids have increased. In July, a man died after falling from a building as he tried to escape agents during a chaotic raid and counter-protest at a cannabis farm in California.

No choice

In Ventura County, California, Ana, 44, whose name has also been changed, is still going to work cleaning and processing vegetables on a farm.

The undocumented single mother of three said she has no choice but to work in the fields out of economic necessity, although she too is frightened when she leaves home.

"I look at my children and I say, 'I don't know if I'm going to come back,'" she told Context.

"And I always tell them that I love them very much," she added.

Crews package table grapes for shipment to supermarkets right in the vineyard in Kern County, California, August 26, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons

Crews package table grapes for shipment to supermarkets right in the vineyard in Kern County, California, August 26, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rachel Parsons

About half of undocumented women in the U.S. are mothers of school-age children and bear the outsized share of caregiving of elders or other family members, according to the Gender Equity Policy Institute (GEPI), a non-profit organisation based in Los Angeles.

That fact is intentionally absent from the Trump administration's messaging about immigrants being criminals, said Nancy Cohen, CEO and founder of GEPI.

"Women immigrants have been disappeared from the debate by Trump and his enablers because that's the only way they can get away with these illegal and cruel raids,” Cohen said.

"As soon as you think about this population being roughly half women with lots of children, that whole visual of the criminal immigrant man collapses," she said.

For undocumented women, the threat of deportation adds insult to injury, as they are already paid less than their male coworkers.

In California, undocumented women in all categories of work make 87 cents for every dollar paid to undocumented men and 58 cents for every dollar paid to men in the general population, according to a report by GEPI.

Women have made up about 12% of those arrested by ICE this year, according to the Deportation Data Project, which collects government immigration enforcement information. The figure does not include arrests by other agencies such as Customs and Border Protection.

More than one third of the nation's agricultural workforce is female, according to U.S. Census data, and experts estimate as many as 40% of undocumented farm workers are women, although it is impossible to determine the exact number.

"Women play a huge role.... Many of them are mothers and many of them are single mothers,” said Teresa Romero, president of United Farm Workers (UFW), a national union.

"So they have two full-time jobs, and they're as experienced, as efficient, as professional as the men are,” she said.

For women without legal authorisation in California, agriculture is the second largest source of employment after domestic labour, according to Cohen's research.

Given the potentially devastating loss of income, UFW does not advise labourers as to whether they should go to work. Instead, it asks farm owners with union contracts to deny immigration agents access to their farms.

Without undocumented workers, California agriculture's gross domestic product would contract by 14%, according to June research by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute.

Grapes are the state's second most valuable crop by revenue after dairy, bringing in $5.5 billion in annual revenue, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

When women in particular are deported, adverse economic impacts ripple across entire communities, threatening to reverse years of gains reflected in decreased poverty rates and rising incomes in the U.S., experts say.

Ana, like many immigrants, regularly sends money home to relatives in Mexico.

Studies suggest that women send slightly more of their earnings to their home countries via remittances than do male immigrants.

Also, when women are deported with children who are U.S. citizens, the already shrinking future American labour force is further diminished.

In fact, a recent report from the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, recommended expanding immigration to help fill jobs left by an ageing workforce and declining domestic birth rate.

In one respect, Maria is fortunate because she is married and her husband is still working. But that does not lessen her anxiety.

If she were to be deported to Mexico, it would rip her family in two. Her son, a young adult, would stay while she would take her daughter with her, she said.

Ana is making a contingency plan to keep her children, all of them citizens, in the U.S. if she is deported. She dreams of them completing their education.

"That's why I'm here holding on for my children," Ana said, adding that she has always paid taxes and has no criminal record.

"In this country, I have had a lot of opportunity because I have dedicated myself to working in the fields and doing well," she said.

"We are good people."

(Reporting by Rachel Parsons. Editing by Anastasia Moloney and Ellen Wulfhorst.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Gender equity

- Workers' rights

- Economic inclusion